1st Maryland History

The 1st Maryland was active from 1776 – 1783.

In 1776 the 1st Maryland was composed of 728 soldiers, by 1781, the regiment was re-organised into 611 soldiers.

The 1st Maryland was part of the “Maryland Line” one of the several units from Maryland.

The 1st Maryland took part in the following engagements:-

Brooklyn – 27th August 1776

Harlem Heights – 16th September 1776

White Plains – 28th October 1776

Trenton – 26th December 1776

Princeton – 3rd January 1777

Brandywine – 11th September 1777

Germantown – 4th October 1777

Monmouth – 28th June 1778

Camden – 16th August 1780

Cowpens – 17th January 1781

Guilford Court House – 15th March 1781

Siege of Yorktown – 28th September – 19th October 1781

The 1st Maryland Regiment (Smallwood’s Regiment) originated with the authorization of a Maryland Battalion of the Maryland State Troops on 14 January 1776. It was organized in the spring at Baltimore, Maryland (three companies) and Annapolis, Maryland (six companies) under the command of Colonel William Smallwood consisting of eight companies and one light infantry company from the northern and western counties of the colony of Maryland.

On 6 July 1776, the Maryland Battalion was assigned to the main Continental Army. On 12 August 1776, it was assigned to Stirling’s Brigade and five days later (17 August 1776) adopted into the main Continental Army. On 31 August, the Maryland Battalion was reassigned from Stirling’s Brigade to McDougall’s Brigade. On 19 September 1776 the Maryland Independent Companies were assigned to the Maryland Battalion. This element was relieved from McDougall’s Brigade on 10 November 1776. From 10 December 1776 to January 1777, the element was assigned to Mercer’s Brigade. In January 1777 this element was re-organized to eight companies and was re-designated as the 1st Maryland Regiment and assigned to the 1st Maryland Brigade on 22 May 1777 of the main continental Army. On 12 May 1779, the regiment was re-organized to nine companies. On 5 April 1780, the 1st Maryland Brigade was reassigned to the Southern Department. On 1 January 1781, it was reassigned to the Maryland Brigade of the Southern Department. The regiment would see action during the New York Campaign, Battle of Trenton, Battle of Princeton, Battle of Brandywine, Battle of Germantown, Battle of Monmouth, Battle of Camden and the Battle of Guilford Court House. The regiment was furloughed 27 July 1783 at Baltimore and disbanded on 15 November 1783.

The Maryland Battalion distinguished itself at the Battle of Long Island by single-handedly covering the retreat of the American forces against numerically superior British and Hessian forces, with a group of men memorialized as the Maryland 400. Thereafter, General George Washington relied heavily upon the Marylanders as one of the few reliable fighting units in the early Continental Army. For this reason, Maryland is sometimes known as “The Old Line State.” The lineage of this unit is perpetuated by the 175th Infantry Regiment, Maryland Army National Guard.

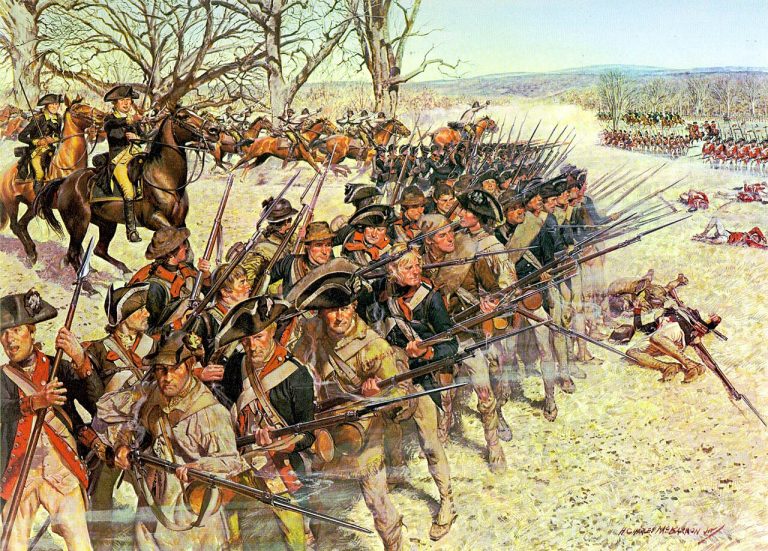

“Battle of Long Island” The Maryland 400, painting by Alonzo Chappel, 1858.

Battle Of Brooklyn

The Maryland Regiment had joined the Continental Army barely two weeks before the Battle of Long Island. Unlike most of Washington’s Army, the Maryland contingent had been well drilled at home and were so well equipped – they even had bayonets, a rarity for the Army – that the Regiment was known at home as the Dandy Fifth, and to the rest of the Army as “Macaronis”, the then current word for dandies. The Marylanders were put under Lord Stirling’s brigade. When the British under Cornwallis surprised the Americans by circling around their rear, Stirling ordered all forces, other than the Marylanders, who were outside the fortified position on Brooklyn Heights to retreat there leaving behind himself and 4 companies of the 1st Maryland. Stirling led these men (who would come to be known as “The Maryland 400”) against Cornwallis’ 2,000 British soldiers who were massed around the Old Stone House, a thick-walled fieldstone and brick fortification near today’s Fifth Avenue and 3rd Street that had been built in 1699 to withstand Indian raids.

In fierce fighting, the Marylanders charged the British forces six times to give their comrades time to make their way to safety with the rest of Washington’s army in the Heights. Twice they managed to drive the British from the house, but as more British reinforcements arrived and the Marylanders casualties mounted, they finally had to give up the assault and try to get to safety themselves. Only Major Mordecai Gist and nine others managed to reach the American lines. Of the others, 256 lay dead in front of the Old Stone House and more than 100 were wounded/and or captured.

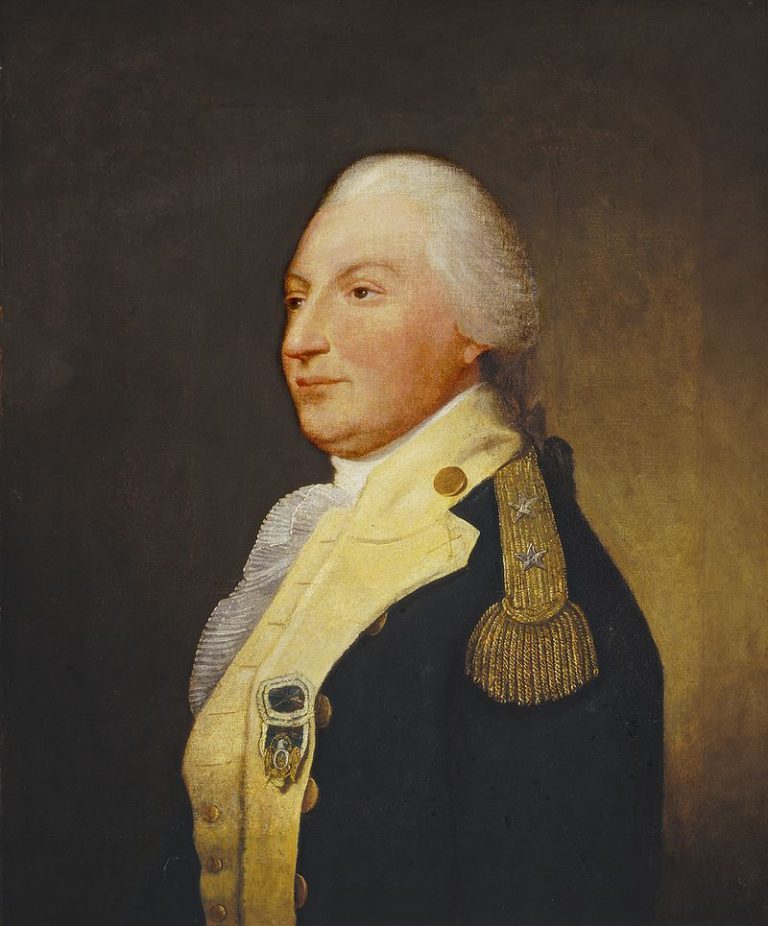

Mordecai Gist

The bravery of the Maryland Regiment earned them the name “immortals”. The dead were buried in a mass grave consisting of six trenches in a farm field. The gravesite is located on what is now Third Avenue between 7th and 8th Streets. Until the widening of Third Avenue in 1910, the site was marked by a tablet that read: “Burial place of ye 256 Maryland soldiers who fell in ye combat at ye Cortelyou House on ye 27th day of August 1776.” The result of the brief battle was stunning for the Americans. More than a thousand men were killed, captured, or missing. Generals Stirling and Sullivan were in the enemy’s hands. The battalion had lost more than 250 of their number. Most of the Marylanders’ casualties occurred in the retreat and desperate covering action at the Cortelyou House. Ultimately, of the original Maryland 400 muster, 96 returned, with only 35 fit for duty.

Historian, Thomas Field, writing in 1869, “The Battle of Long Island,” called the stand of the Marylanders “an hour more precious to liberty than any other in history.” Four companies of the 1st Maryland stood as the final anchor of the crumbled American front line, and their heroic action not only saved many of their fellows but afforded Washington critical respite to regroup and withdraw his battered troops to Manhattan and continue the struggle for independence.

Over time, the farm became the site of a Red Devil paint factory, and the burial grounds became part of a factory courtyard open to the sky because of a deed restriction relating to the grave. More time passed. The paint factory gave way to an auto repair shop and the courtyard was roofed over. Today the heroes whom Washington himself lamented lie under the floor of the building that had housed the auto repair shop. They lie in their unmarked grave miles from a Stanford White monument to their sacrifice in the form of a marble shaft topped with a sphere that stands at the foot of Lookout Hill in Prospect Park. It was erected in 1895 as a gift of the Maryland Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. The Old Stone House survived the battle and in later years became the first clubhouse of the baseball team that came to be known as the Brooklyn Dodgers. It was destroyed in the 1890s, and rebuilt in the 1930s.

“Battle of Guilford Courthouse” 15th March 1781 – from “Soldiers of the American Revolution” by H. Charles McBarron.

Colonel William Smallwood

William Smallwood (1732 – February 14, 1792) was an American planter, soldier and politician from Charles County, Maryland.[1] He served in the American Revolutionary War, rising to the rank of major general. He was serving as the fourth Governor of Maryland when the state adopted the United States Constitution.

Early life and education

Smallwood was born in 1732 to planter Bayne Smallwood (1711–1768) and Priscilla Heaberd or Heabeard (c.1715–1784). He had six siblings: Lucy Heaberd Smallwood (c. 1734-1768, married John Truman Stoddert), Elizabeth Smallwood (born c. 1736, married James Leiper), Margaret Smallwood (born c. 1738, married Walter Truman Stoddert), Heaberd Smallwood (c. 1740–1780), Eleanor Smallwood (born c. 1743 married William Grayson) and Priscilla Heaberd Smallwood (c. 1750–1815, married John Courts in 1794). His sister Eleanor and brother Heaberd served with him later in the American Revolutionary War.

His parents sent the boys to England, for their education at Eton. His great-grandfather was James Smallwood, who immigrated in 1664 and became a member of the Maryland Assembly in 1692. James’ son Bayne (1685–1709) followed him later in the Assembly. Bayne (1711–1775) and his sister Hester were the great-great-grandchildren of Maryland Governor William Stone; Hester (Smallwood) Smith’s daughter-in-law Sarah (Butler) Stone was the grandmother of James Butler Bonham and Milledge Luke Bonham. A first cousin of James and Milledge Bonham was Senator Matthew Butler.

Smallwood served as an officer during the French and Indian War, the North American theater of the Seven Years’ War, and was elected to the pre-Revolution colonial-era provincial assembly for the Province of Maryland.

William Smallwood

When the American Revolutionary War began, Smallwood was appointed a colonel of the 1st Maryland Regiment in 1776. He led the regiment in the New York and New Jersey campaign.

For their role in the Battle of Brooklyn on August 27, 1776, when the Maryland Regiment heroically covered the hasty retreat of the routed Continental Army, General George Washington promoted Smallwood to brigadier general. Washington bestowed on the regiment a future state nickname, “Old Line State”, in reference to the extreme sacrifice of the Maryland 400 to hold the line at the Old Stone House against a vastly superior force of British and Hessian troops while suffering massive casualties, roughly 70 percent of whom were killed in action. Shortly thereafter, Smallwood led what remained of his regiment to fight “alongside soldiers from Connecticut, Delaware, and New York” in the Battle of White Plains, when he was twice wounded but “prevented the destruction of the entire Continental Army”.

On December 21, 1777, Smallwood commanded 1,500 Delaware and Maryland troops at the Continental Army Encampment Site on the east side of Brandywine Creek, to prevent occupation of Wilmington by the British and to protect the flour mills on the Brandywine. He continued to serve under George Washington in the Philadelphia campaign, where his regiment again distinguished itself at Germantown. He was then quartered at Foulke House, which was occupied by the family of Sally Wister.

In 1780, he was a part of General Horatio Gates’ army that was routed at Camden, South Carolina; his brigade was among the formations that held their ground, garnering Smallwood a promotion to major general. Smallwood’s accounts of the battle and criticisms of Gates’ behavior before and during the battle may have contributed to the Congressional inquiries into the debacle. Opposed to the hiring and promotion of foreigners, Smallwood objected to working under Baron von Steuben. Smallwood briefly commanded the militia forces of North Carolina in late 1780 and early 1781 before returning to Maryland, staying there for the remainder of the war. He resigned from the Continental Army in 1783 and later that year was elected to serve as the first president of the newly established Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland.

Maryland governor

Smallwood was elected to Congress in 1784, but before he could take his seat, the Legislature chose him to succeed William Paca as Governor of Maryland. He qualified on November 26, 1785, and served the customary three terms, retiring from his gubernatorial office on November 24, 1788. Smallwood had the misfortune of serving as governor during one of the most difficult periods in the history of the nation. Not only were the Articles of Confederation proving inoperable, but the country also found itself in the midst of an economic depression. In spite of the country’s unsettled affairs, Smallwood was responsible for several major accomplishments, including convening the state’s convention that ratified the United States Constitution, despite strong opposition to the proposed document in the State.

Later years

Smallwood never married. The 1790 United States census reveals that he held 56 slaves and a yearly tobacco crop of 3000 pounds.

When he died in 1792, his estate, known as Mattawoman, including his home the Retreat, passed to his sister Eleanor who married Colonel William Grayson of Virginia. William Truman Stoddert, Smallwood’s nephew, was orphaned at age nine and raised by his maternal grandfather, Bayne Smallwood. Stoddert also served in the Maryland Line and was admitted as an original member of the Society of the Cincinnati in Maryland.

Mordecai Gist

Mordecai Gist (1743–1792) was a member of a prominent Maryland family who became a brigadier general in command of the Maryland Line in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War.

Gist was born February 22, 1742/3 in Baltimore, Maryland (one source says Reisterstown, Maryland), the fourth child of Thomas and Susannah (Cockey) Gist. Thomas Gist’s father, Captain Richard Gist (1684 – August 28, 1741), was the surveyor of Maryland’s Eastern Shore and one of the commissioners who laid out Baltimore Town in 1729. Richard Gist’s father, Christopher Gist (1655 or 1659 – Feb. 1690), was an English immigrant who came to the Province of Maryland before 1682 and settled in “South Canton” on the south bank of the Patapsco River. Christopher Gist married Edith Cromwell (1660–1694).

Gist was the nephew of Christopher Gist (1706–1759). This Christopher Gist was a Colonial-era explorer, scout, and frontier settler who was employed by the Ohio Company and had served with 21-year-old Colonel George Washington. (Christopher Gist is credited with twice saving Washington’s life when they were surveying land in the Ohio country in 1753.) Mordecai Gist was also distantly related to John Eager Howard.

Mordecai Gist was educated for commercial pursuits. At the beginning of the American Revolution, the young men of Baltimore associated under the title of the “Baltimore Independent Company” and elected Gist as their captain. It was the first company raised in Maryland for the defence of popular liberty.

Mordecai Gist

Revolutionary War service

In 1776, Gist was appointed major of Smallwood’s Maryland Regiment, and was with them in the Battle of Long Island, where they fought a delaying action at the Old Stone House (Brooklyn, New York), allowing the American army to escape encirclement.

In January 1779, the Continental Congress appointed him as a brigadier general in the Continental Army, and he took the command of the 2nd Maryland Brigade. He fought stubbornly at the Battle of Camden in South Carolina in 1780. At one time after a bayonet charge, his force secured fifty prisoners, but the British under Lord Cornwallis rallied, and the Marylanders gave way. Gist escaped, and, a year later, he was present at the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown. (Gist appears (back row, right side) in John Trumbull’s painting Surrender of Lord Cornwallis which hangs in the rotunda of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C.)

He joined the southern army under Nathanael Greene, and he was given the command of the light corps again when the army was re-modeled in 1782. On August 26, 1782, he rallied the broken forces of the Americans under John Laurens after they had been scattered in an ambush set by a British foraging party.

After the war

After the war, Gist relocated to a plantation near Charleston, South Carolina. He was admitted as an original member of The Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland and was elected as the first vice president of the Maryland Society on November 22, 1783. He later transferred his membership to the South Carolina Society. Gist also served as the grand master of Freemasons in South Carolina.

He had two children that lived to adulthood, both sons, one of whom he named “Independent” and the other “States.” Various sources suggest he died between August and September 1792, at the age of 49, in Charleston, but his will was written on the “First day of September” and probated the following month on October 19, 1792. He is buried in St. Michael’s Churchyard next to his son, States Gist, and daughter Susannah Gist.

Mordecai Gist was distantly related to States Rights Gist, a brigadier general in the Confederate army during the American Civil War who died of wounds received while leading his brigade in a charge against U.S. fortifications at the Battle of Franklin in November 1864. States Rights Gist was the grandson of William Gist (born 1711), cousin of Mordecai Gist.

John Gunby

John Gunby (March 10, 1745 – May 17, 1807) was an American planter and soldier from Somerset County, Maryland, who is considered by many to be “one of the most gallant officers of the Maryland Line under Gen. Smallwood”. He entered service volunteering as a minuteman in 1775 and fought for the American cause until the end earning praise as probably the most brilliant soldier whom Maryland contributed to the War of Independence. Gunby was also the grandfather of Senator Ephraim King Wilson II.

Early life

The Gunby family arrived in Maryland around 1660, coming from Yorkshire, England, and settling in Queen Anne’s County. Around 1710, his grandfather moved the family to Somerset County to a farm at Gunby’s Creek, an inlet of Pocomoke Bay, near present-day Crisfield where John Gunby was born on March 10, 1745. During his youth, Gunby had many opportunities to deal with persons from different social classes as the Gunby home was considered a rendezvous for the people of the neighbouring country and the family exercised substantial influence due to their large land holdings and sea vessels with which they engaged in coastal trade.

In the spring of 1775, at the age of 30, Gunby volunteered as a minuteman, for which his father, a staunch loyalist, warned him that he was running the risk of being hanged as a traitor. John Gunby is said to have replied:

I am determined to join American forces, come what will. We have little fear, for justice will dominate, and the colonies, as victors, will live to adopt a crown of freedom, not one of oppression. Your arguments, your entreaties your commands will avail nothing. For me, I would rather sink into a patriot’s grave then wear the crown of England.

Early War

When the Revolution began, Gunby joined the American forces and formed an independent military company at his own expense. The equipping and maintaining of this company, which was among the first to be organized, cost Gunby most of his wealth. The company, including officers, numbered a hundred and three men. On January 2, 1776, he was elected captain of the 2nd Independent Maryland Company – Somerset County.

In the early part of the War, Gunby’s company spent much of their time patrolling southern Maryland and breaking up Tory camps which were to be found on the lower part of the peninsula as Somerset County was a leading Tory stronghold. On August 16, 1776, the 2nd Independent Maryland Company was ordered north to join General George Washington’s army as part of Maryland’s quota of troops towards the Continental Army.

Southern Campaign

After the unsuccessful attempt to capture Savannah, Georgia, under the command of General Benjamin Lincoln, the Southern Department of the Continental Army retreated to Charleston, South Carolina. General Sir Henry Clinton moved his forces, surrounded the city where Lincoln’s army had taken refuge and cut off any chance of relief for the Continental Army. Prior to his surrender, Lincoln had been able to get messages to General Washington and the Continental Congress requesting aid. At the end of April 1780, Washington dispatched General deKalb with 1,400 Maryland and Delaware troops. The Maryland Line made up a large portion of this force.

General deKalb’s forces took almost a month to descend the Chesapeake Bay and did not arrive in Petersburg, Virginia, until the middle of June, almost a month after Lincoln had surrendered his army. The Continental Congress appointed Horatio Gates to command the Southern Department. He assumed command on July 25, 1780, and immediately marched into South Carolina with the intent of engaging the British Army, now under the command of Charles Cornwallis.

Battle of Camden

After brief aggressive manoeuvring which threatened the British position in the Carolinas, Cornwallis moved his forces to engage the American forces. The two armies engaged one another in the Battle of Camden on August 16, 1780, six miles north of Camden, South Carolina. Due to several tactical errors on the part of Horatio Gates, the British were able to achieve a decisive victory. The Maryland Troops, Gunby’s company among them, deserted by their commander fought until they were pressed on all sides and forced to retreat. Two-fifths of the Marylanders were killed or wounded and General deKalb was mortally wounded. Prior to his death three days later, deKalb paid a glowing tribute to the Maryland Troop under his command.

Battle of Guilford Court House

After the successful retreat across the Dan River, General Greene chose to offer battle to General Cornwallis’s forces on March 15, 1781, on ground of his own choosing at Guliford Court House, inside the city limits of present-day Greensboro, North Carolina.

After the British forces had broken Greene’s first line made up of North Carolina Militia and the second line made up of Virginia Militia, they threatened the third line made up by the 1st Maryland Regiment, under the command of Gunby, and the 2nd Maryland Regiment. The Brigade of Guards, under the command of a Colonel Stewart, broke through the 2nd Maryland Regiment, captured two field pieces and threatened the rear of Gunby’s forces, who were already engaged with sizable force under the command of a Colonel Webster.

Gunby, his command threatened on two fronts, ordered a fierce charge and swept Webster’s forces from the field. He then wheeled his troops to face the oncoming guards unit. After a brief exchange of musket fire, in which Gunby’s horse was shot from under him, the 1st Maryland Regiment charged the Guards unit, who were quickly routed.

Greene, not able to see this part of the battle from his vantage point, had already ordered a retreat. Thus, unsupported, the Maryland troops were soon forced to withdraw.

The Battle of Hobkirk’s Hill

After Guilford Court House, Cornwallis’s force was spent and in great need of supply. He therefore moved his army towards Wilmington, North Carolina where he had previously ordered supplies to be sent. Greene pursued the British force for a short time before deciding to take his forces into South Carolina. Greene hoped that by threatening the British garrisons in the state he could force Cornwallis to pursue him and then engage the British on ground favourable to his army. When Cornwallis did not pursue the Continental Army, Greene chose to reduce the British garrisons scattered throughout South Carolina in order to force the British back into Charleston.

To this end, General Greene moved his main force—made up of two Virginia and two Maryland regiments of Continentals as well as a force of Cavalry under William Washington—with all possible speed towards Camden, South Carolina where Lord Francis Rawdon was stationed with 900 troops. Rawdon learned of Greene’s approach and readied his forces to repel an attack. Upon arriving at Camden, and finding his planned assault impractical, Greene retired his forces to a low heavily wooded ridge locally called Hobkirk’s Hill.

Having received intelligence from a deserter on April 24 that the Continental Artillery and Militia had been detached from Greene’s main force, Rawdon decided to attack. However, on the morning of April 25, 1781 Lieutenant Colonel Carrington had brought the artillery back to Hobkirk’s Hill along with a supply of provisions which were distributed to the Continental troops. At around 11 am, while many of the Continentals were occupied with cooking and washing clothes, the advanced pickets detected the British forces who had gained the American left by marching a circuit of great distance and keeping close to a swamp that was next to the ridge occupied by the Continental Army.

The advanced pickets, under Captain Robert Kirkwood, were able to delay the British advance giving Greene time to give orders and address his forces distribution. Greene placed the a Virginia Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel Campbell on the extreme right with another Virginia Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Hawes to their left. On the extreme left, Greene placed the 5th Maryland under Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Ford with the 1st Maryland, under Gunby’s command, to their right. The artillery was placed in the centre with North Carolina militia in the rear.

Once having extricated his forces from the woods and forcing the pickets to retreat, Rawdon arrayed his forces and slowly advanced up the ridge towards the waiting Continentals. Greene, perceiving the British forces were presenting a narrow front, ordered an attack. Greene instructed Campbell on the right to wheel his men to the left and engage the British on their flank with Ford to take his men and make a similar movement on the left. Greene ordered the two remaining regiments in the centre to advance with bayonets and confront the enemy head on while Washington was to take his cavalry around the British left flank and attack the enemy in the rear.

During the advance of the 1st Maryland on the British left, Captain William Beatty jr. who was in command on the right of Gunby’s regiment, was killed causing his company to stop their advance. Gunby ordered his men to stop their advance and fall back with the intention of reforming their line. At this time, Benjamin Ford of the 5th Maryland was mortally wounded throwing his troops into disorder. Finding their flank in disarray and being threatened by a company of Irish troops Rawdon had brought up to strengthen his flank, the Maryland troops rallied briefly to fire a few rounds and then left the field in disorder. Seeing this, Rawdon quickly rallied his flagging troops and advanced, taking the field.

Court of inquiry

The day after the Battle of Hobkirk’s Hill, General Greene addressed his troops and presented a pointed comment that Gunby apparently felt this was directed at him and he immediately applied for a court of inquiry to review his actions on the field.[19] His request was granted by General Greene who named General Huger, Colonel Harrison of the artillery and Lieutenant Colonel Washington of the cavalry to conduct the review.

On May 2, the Court published their conclusions:

The Court, whereof Brigadier General Huger is president, appointed to inquire into the conduct Colonel Gunby, in the action of the 25th ultimo, report as follows, namely:

“It appears to the Court that Colonel Gunby received orders to advance with his regiment and charge bayonet without firing. This order he immediately communicated to his regiment which advanced cheerfully for some distance, when a firing began on the right of the regiment, and in a short time became general through it. That soon two companies on the right of the regiment gave way. That Colonel Gunby then gave Lieutenant Colonel Howard orders to bring off the other four companies, which at that time appeared disposed to advance, except a few. That Lieutenant Colonel Howard brought off the four companies from the left and joined Colonel Gunby at the foot of the hill, about sixty yards in the rear. That Lieutenant Colonel Howard there found Colonel Gunby actively exerting himself in rallying the two companies that broke from the right, which he effected, and the regiment was again formed and gave a fire or two at enemy, which appeared on the hill in front. It also appeared from other testimony, that Colonel Gunby, at several other times, was active in rallying and forming his troops.”

It appears, from the above report, that Colonel Gunby’s spirit and activity were unexceptionable. But his order for the regiment to retire, which broke the line, was extremely improper and unmilitary, and, in all probability the only cause why we did not obtain a complete victory.

Greene was firm in his belief that Gunby was the sole reason for the Continental Army’s loss at Hobkirk Hill. On August 6, 1781, in a letter to Joseph Reed, Greene stated his position bluntly:

“The troops were not to blame in the Camden affair; Gunby was the sole cause of the defeat; and I found him much more blameable afterwards, than I represented him in my public letters. The action of Camden was much more bloody, according to the numbers engaged, than that of Guilford on both sides. The enemy had more than one third of their whole force engaged either killed or wounded, and we had no less than a quarter. Depend upon it, our actions have been bloody and severe, according to the force engaged, and we should have had Lord Rawdon and his whole command prisoners in three minutes, if Colonel Gunby had not ordered his regiment to retire, the greatest part of which were advancing rapidly at the time they were ordered off. I was almost frantic with vexation at the disappointment. Fortune has not been our friend”.

Henry Lee, “Light Horse Harry”, gave a different opinion in his memoirs of the war stating that the Maryland troops abandoned their position contrary to the efforts and example of Gunby and the other Continental officers on the field.

It has been pointed out that the tribunal paid no disrespect to Colonel Gunby, pointing out his “spirit and activity”; however, it clearly found him at fault for making an error in military tactics. Both the tribunal’s and Greene’s assertion that Gunby’s order to his regiment to retire and reform was the sole cause for the Continental line breaking does not take into account that the two companies on Gunby’s right had already broken the line and were falling back in confusion upon the death of Captain Beatty. The historian Benson John Lossing attributes the entire loss of victory to the death of Captain Beatty.

Nor did the tribunal or Greene appear to accept that Gunby’s order for the four companies that were still advancing to reform their line to be a proper military tactic. Henry Lee, however, points out that this same manoeuvre had been performed by Daniel Morgan at Cowpens.

In addition, as mentioned in the tribunal’s report, Gunby was apparently successful in rallying his troops who then fired one or two rounds at the oncoming British soldiers which would seem to indicate that the Maryland troops were not panicked as Greene’s comments, the tribunal’s report and Henry Lee’s account seem to allude.

Lee offers another reason for the American defeat at Hobkirk’s Hill, suggesting that Greene’s order to the Cavalry under Williams to circle around the British and attack them in the rear was a plausible explanation for the loss. As explained in his memoirs, if the Cavalry had been held in reserve, rather than order to attack the rear of the British force where they were held up by Rowsan’s baggage train, William’s troops could have been used to reinforce the line and reversing the gains made by the British reserve that had already been committed to the battle.

Regardless that both the tribunal and Greene found fault with Gunby for his actions at Hobkirk Hill, Gunby was retained as commander of the 1st Maryland Regiment.

Later war

The Maryland Line continued to distinguish itself in the later battles of the Southern theater of the American Revolutionary War with Gunby continuing to command the 1st Maryland Regiment.

Of the Maryland Line’s actions at the Battle of Eutaw Springs, General Greene wrote in his official report of the engagement:

“Nothing could exceed the gallantry and firmness of both officers and soldiers upon this occasion. They preserved their order and pressed on with such unshaken resolution that they bore down all before them.”

Gunby continued in the capacity of commander of the 1st Maryland Regiment until the regiment was furloughed and all of its business concluded. Prior to his resigning his commission, he was given a brevet promotion to brigadier general on September 30, 1783.

Life after war

After mustering out of the Continental Army, Gunby returned home to Somerset County, Maryland. His father, who died in 1788, bequeathed him a large farm in Worcester County, Maryland, two miles south of Snow Hill. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Gunby avoided politics or using his fame from the war for personal gain. He kept to his farm devoting himself to agriculture. For some years he supported at least three families of Maryland officers killed during the Carolina Campaigns. Gunby was also known to help poor families build houses and awaiting their convenience for payment, promoting the construction of new roads, furnishing horse teams for those in need and contributing toward the maintenance of places of worship. Brigadier General Gunby was admitted as an original member of the Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland.

1st Maryland Roster

Finding the Maryland 400, is an organisation dedicated to Maryland’s first Revolutionary War soldiers, who saved the Continental Army in

1776.