© Claire Morris 2003-2024

ADDENDUM

THE IRISH BRIGADE & IT’S PRIESTS

The Irish Brigade were very fortunate that there was so much provision for the men’s religious needs. The Brigade, which was almost exclusively Catholic, had at its peak three Catholic priests, and at no point during the war was the Brigade without one.

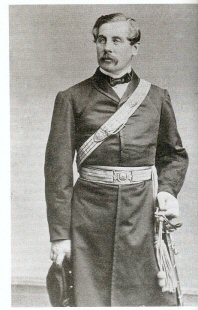

Father Dillion of the 63rd New York was from Notre-Dame, Father Corby the mild mannered and understanding chaplain of the 88th New York, was also from Notre-Dame, and Father Ouellet was a Jesuit Catholic Priest from Fordham for the 69th New York.

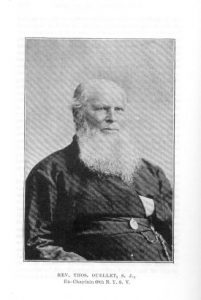

Father Ouellet was a short burly man who had a long beard down to his chest. The author Paul Jones believes that Father Ouellet was an “Uncompromising martinet on all matters concerning religious duties. In spite of his quick temper, the men liked him because he was just as likely to reprove an officer publicly for excessive profanity as he was to admonish a private in the rear rank,” (Jones pg 97). He was with the 69th New York from November 1861 until the summer of 1862. He was actually discharged from the 69th on 25th December 1862, but again he re-enlisted on the 15th April 1864 and continued until the end of the war. In between his two periods of service with the 69th, Father Oullet was the hospital chaplain in Newbern, North Carolina, still serving the Union. Father Edward McKee was the chaplain of the 116th Pennsylvania from 24th September 1862 to 21st December 1862, when he was honourably discharged after suffering illness for some time. Father Dillon worked hard to ensure that the men of the 63rd New York were ‘Temperance Men’ who took the pledge at Father Dillon’s urgings, to abstain from alcohol for the duration of the war.

There were always ample opportunities for the men to hear mass, take communion and to go to confession. Many Catholics in the Army of the Potomac were not so fortunate, and they would, when given the opportunity visit the Irish Brigade to see the priests.

The priest’s did more than perform the Catholic religious ceremonies. They were guardians of ‘moral fibre’ encouraging temperance and personal cleanliness whilst on campaign. They also helped with the organisation of the St Patrick’s Day’s celebrations, and assisted the men sending money home to their families in New York, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts. For those soldiers who were not as literate as others, the Irish Brigade priests wrote letters home on behalf of the men. As Father Corby was one of the few Catholic priests in the Army Of The Potomac, he had to prepare several men from various Corps for executions after their court marshals. These understandably had a profound effect on Father Corby, and several of these accounts litter his memoirs.

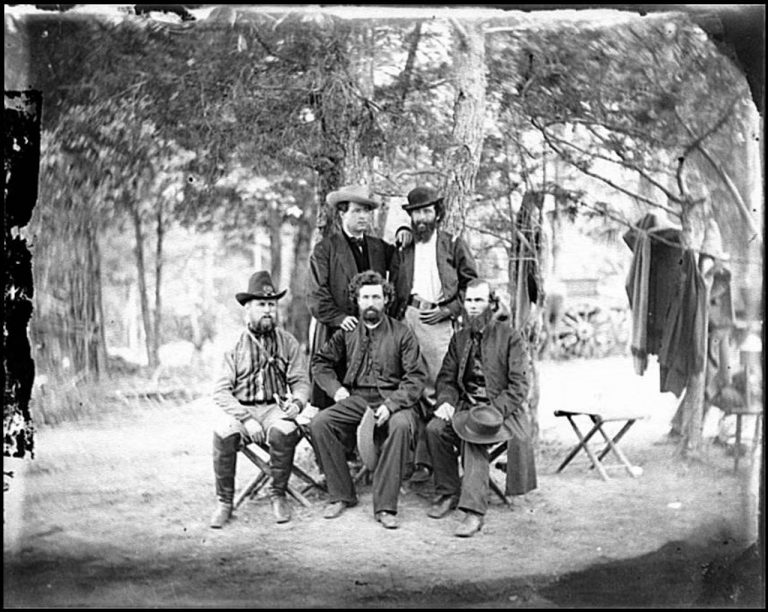

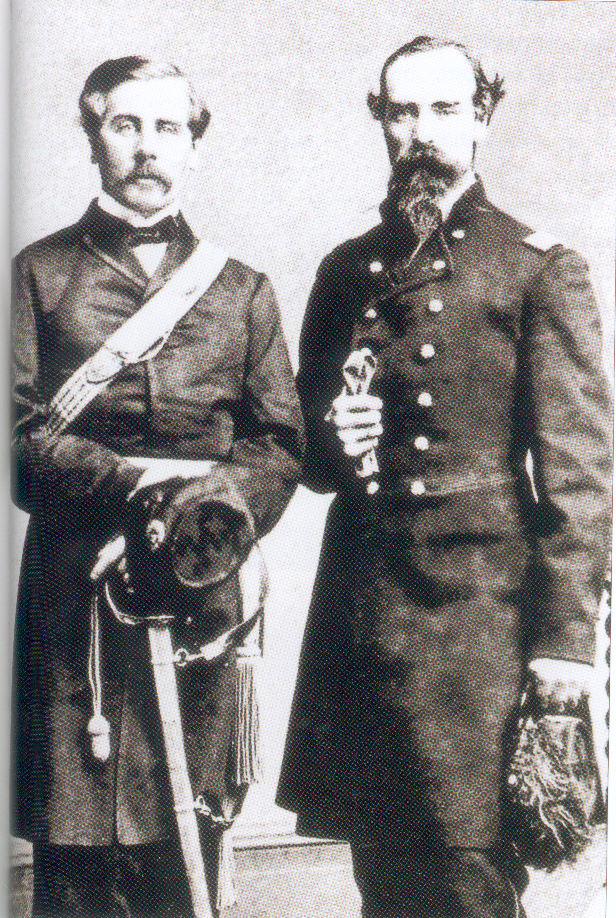

Irish Brigade chaplains at Harrison’s Landing, Virginia, during the Peninsular Campaign in 1862.

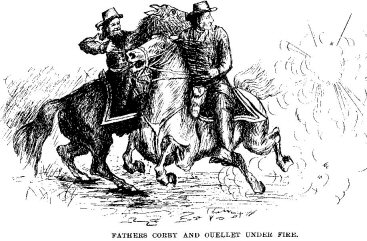

Both Father Corby and Ouellet showed great courage in going forward with the men during battle, and performing their religious duties whilst often under severe fire, searching for wounded men to comfort them, and when necessary perform the last rites. After battles they would also stay at field hospitals administering rites to those who requested them, and generally caring for the wounded.

St. Clair A Mullholland in his history, ‘The Story Of The One Hundred & Sixteenth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers In The War Of Rebellion: The Record Of A Gallant Command,’ states that, “At the time it did not occur to one, but now, when years have passed and we look back we must feel astonished at the high moral standard of the army that fought the War of the Rebellion, and the Regiment was second to none in that respect. Seldom was an obscene word or an oath heard in the camp. Meetings for prayer were of almost daily occurrence, and the groups of men sitting on the ground or gathered on the hill side listening to the Gospel were strong remaindered of the mounds of Galilee when the people sat upon the ground to hear the Saviour teach.”

Father Corby & Oullet under fire at Petersburg, 1864.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION, LETTERS,

APPENDIX & QUOTES

WEAPONS

The 69th New York were still using their .69 calibre smoothbore muskets during the fighting in Gettysburg.

CAMP LIFE AT NIGHT

In his memoirs Father Corby alludes to camp life, “Good brass bands in camp lent a most agreeable service. While the soldiers enjoyed their campfire chats, the bands were playing at various points and gave a romantic charm to the situation. Picture to yourself thousands of white tents among beautiful green trees, with the fires glimmering here and there for miles over an extended plain, furnishing light and comfort to over a hundred thousand armed men, while darkness gently spreads its mantle over all. As the hours creep into the night, the campfires show to more advantage, especially when you can imagine how the scene is animated by varied conversations – some droll and witty, some grave and touching, many concerning the great, sublime future. In this you have a faint picture of our camp at night,” (Corby pg 96).

FOOD

During their early training in the autumn and winter of 1861 and 1862 the food received by the men was of a good quality and very regular, a testament to the organisation skills of those in charge of the Federal supply departments, and to the man in charge of the army, McClellan. “The commissary even introduced novelties, received with caution, but approved after a trial. One was pressed vegetable soup, a dried mixture of cooked potatoes, onions, beans, lettuce, garlic, parsley, parsnips and carrots, rationed out in twists like a plug of tobacco. Hot water and a mess tin converted it into a nourishing soup that reminded the Irish Brigade of the free lunch they used to get at the Dutchman’s in New York. If they keep feeding us that, one soldier wrote home, I’ll be talking German in two weeks,” (Jones pg 78).

Throughout the civil war the daily food allowance for each Federal soldier was “Twelve ounces of pork or bacon, or, one pound and four ounces of salt or fresh beef; one pound and six ounces of soft bread or flour, or, one pound of hard bread, or, one pound and four ounces of corn meal; and to every one hundred rations, fifteen pounds of beans or peas, and ten pounds of rice or hominy; ten pounds of green coffee, or, eight pounds of roasted (or roasted and ground) coffee, or, one pound and eight ounces of tea; fifteen pounds of sugar; four quarts of vinegar…three pounds and twelve ounces of salt; four ounces of pepper; thirty pounds of potatoes, when practicable, and one quart of molasses,” (Kohl pg 48).

PARCELS

Soldiers would often ask for items to be sent from home, little luxuries to help supplement their diet, or to replace lost or worn clothing, or local newspapers so they could keep abreast of events at home. These little luxuries and mementoes from home were huge moral boosters. Irish Brigade soldier Sergeant Peter Welsh from the 28th Massachusetts asked his wife to send him items from home; “…if you send anything be shure to send some tobaco it is very dear here plug cavendish is what I want if you have not any of the articles bought you had better not mind them but if you are sending them get a small box and put them in and nail it up you could get a small box at the grocery store that would suit…” (Kohl pg 117).

On the receipt of the parcel, Welsh wrote back to his wife, on 28th August 1863, “…The box had been opened but all you sent came safe the provost guard open all the boxes to search for liquor as it is not alowed come to any soldier there was the tobaco pipe the cheese prayer book paper envelopes penholder two towls one poket handerchief two bottles of pickles and two combs and ink bottle All the articals you sent were just what suited and they are twice as good to me on acount of you having sent them…” (Kohl pg 121).

SUTLERS & WOMEN WITH THE IRISH BRIGADE

There are very few references to women or Sutlers with the Irish Brigade. Welsh states that, “My dear wife you have been misinformed about Suttlers being alowed to sell licquor here. They are not alowed to sell it to inlisted men but they are alowed to sell it to officers untill lately but they are not alowed to bring it here under any pretence now unless they can smugle it in of course they used to sell it to soldiers when they had it for the big profit made from the price they sold it at was to strong a temptation…but by selling to soldiers their whole stock horses hent wagons and every thing they had were liable to be conviscated and themselves sent outside the line with orders not to return again that is the Provost Marshals business and I have seen it done with several Suttlers…We [had] cases of this in our brigade quite lately but they were not sutlers one was a woman that cooked for Colonel Kelly who is acting Brig’r General her husband is a private in the 88th and she has been with him ever since the brigade came out she managed in some way to get licquor and used to put in about half water and then sell it for five dollars a canteen which olds about three pints she was sent to prison in Washington…” (Kohl pg 128).

In talking about the battle of Malvern Hill, Corby states that, “During the second day’s fight, two or three women, wives of soldiers, accompanied the Brigade, and one of them, Mary Gordan, wife of a soldier of Company H., Eighty-eighth New York, especially distinguished herself in caring for the wounded, tearing into strips her very underclothing to bind up the wounds. With a rugged nature, but a kind, and noble heart, she remained with the men on parts of the field where surgeons seldom ventured, and by her prompt action she often saved the life-blood that was fast ebbing away; and was the means of saving many a life. Gen. Sumner saw her thus occupied at Savage Station, and when our troops reached Harrison’s Landing, he had her made brigade sutler, and gave her permission to pass free to Washington and back, all in government boats,” (Corby pg 370).

LETTERS REGARDING THE IRISH BRIGADE

WAR DEPARTMENT, WASHINGTON.

August 30, 1861

COLONEL THOMAS F. MEAGHER, New York

SIR – The Regiment of infantry known as the Sixth-ninth Infantry, which you offer, is accepted for three years, or during the war, provided you have it ready for marching orders in thirty days. This acceptance is with the distinct understanding that this department will revoke the commissions of all officers who may be found incompetent for the proper discharge of their duties.

Your men will be mustered into the United States service in accordance with General Orders Nos. 58 and 61.

You are further authorized to arrange with the colonels commanding of four other regiments to be raised to form a brigade, the brigadier-general for which will be designated hereafter by the proper authority of Government.

Very respectfully your obedient servant,

THOMAS A. SCOTT.

Assistant Secretary of War.

(Whilst the Irish Brigade was camped at Harrison’s Landing Virginia, after the heavy fighting of the Seven Days battles, at the end of July 1862, General Meagher and his aides returned to New York for recruits. At a rally he read the following letter [taken from Coyngham’s book])

BELLEVUE HOSPITAL, NEW YORK CITY,

July 26, 1862.

BELOVED GENERAL:- I cannot describe to you the pride and contentment I experienced on ascertaining through the newspapers the news of your arrival in this city, as I then felt assured that you had escaped the storm of July 1st unharmed, notwithstanding your exposed and conspicuous position, while leading your gallant band to the contest. I came here on the Vanderbilt. I was a prisoner in Richmond for eighteen days, during which time I suffered intensely from my wounds, the humiliation of being in rebel hands, and a scorching fever; but when delivered from the contagion of their despotic atmosphere, and placed once more under the “Old Flag,” I became revived and refreshed, and have been on the gain ever since.

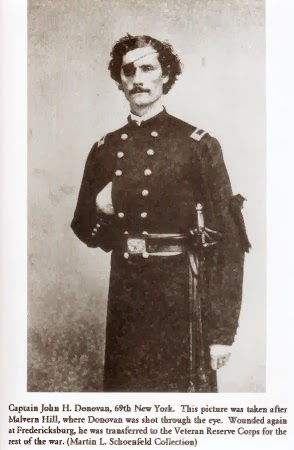

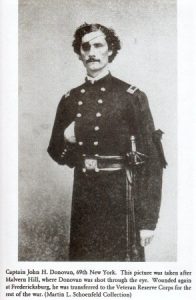

I received a very severe wound during our second engagement with the enemy, while in the act, with other officers, of rallying our left wing, which was being hard pressed, and on the point of being outflanked by a numerous force of the enemy. The ball carried away part of the right ear, entering the skull and passing through the right eye, totally destroying it. When taken to the hospital, the doctors pronounced it fatal, but I was determined not to “give up the ship:” Next morning, the 2d July, I found myself totally eclipsed, and remained so for four days. Generals Hill and Magruder visited the wounded the morning after the battle. General Hill went round to the several officers, and demanded their sidearms and revolvers, which they delivered up with reluctance. The general demanded mine. I told him I had taken occasion to have them sent to my regiment the night previous. He replied that, from the apparent nature of my wounds, I wouldn’t have much need of them in the future. I told him that I had one good eye left, and that I would still risk it in the cause of the old Union; and that, should fate deprive me of that, I would “go it blind,” until rebellion was put down, and the supremacy of the Federal Government established. He asked me the name of my regiment. I told him the name of my regiment and brigade with the greatest pride, when the general quietly passed away. I was told at Richmond, that had they known the precise whereabouts of the Irish Brigade on the field they would have sent a whole division to take itself and General Meagher prisoners, and hang the “exiled traitor” from the highest tree in Richmond. I told them that they would need several divisions to accomplish that job, and that even then they couldn’t do it.

I am pleased to tell you that Major O’Neill is unharmed, with the exception of a slight bruise in the arm, from a piece of shell. He is prisoner in Richmond, in company with Generals McCall, Reynolds, and numerous other officers. The major visited me under a heavy guard as an escort. He felt rather indisposed, and as uneasy as a caged tiger. I am much grieved at our heavy losses, but heartily proud that we have maintained the honour of the two flags which we so proudly and jealously bore, as well as the military prestige of our noble old race. In conclusion, I have the honour to be, most esteemed general, your obedient servant,

John H Donovan, Lieutenant,

Company D, 69th Regiment, Irish Brigade.

After the battle of Malvern Hill, Andrew Birmingham, a Lieutenant in the 69th at Harrison’s Landing, wrote to a friend in New York who had just been exchanged, after a year in Libby Prison:

“I suppose you had a great time in Richmond. I wish you would write to me and let me know what kind of treatment you got there, and how does the colonel (Corcoran) stand it. We were within four miles of that noted town for over a month, but after all ,trees where we were, and little did I think that we would ever go any further away from it without first seeing it, but such things will be.

“All owing to the damned abolitionists that are in Congress, that spent over a couple of weeks talking about the White House on the Pamunkey River instead of doing something for the army. If we only had about 20,000 more men, which we should have, we would be in Richmond today instead of where we are. But no, Congress would rather talk about why such and such a house was not a hospital for soldiers. There would not be half the hospitals required today nor half the wives widowed or children fatherless, if something had been done,” (Jones pg 95).

8th May 1863, Meagher wrote the following resignation letter to Divisional headquarters:-

“I beg most respectively to tender you, and through you the proper authorities, my resignation as Brigadier General commanding what was once known as the Irish Brigade. That Brigade no longer exists. The assault on the enemy 13th December last reduced it to something less than a minimum regiment of infantry. For several weeks it remained in this exhausted condition. Brave fellows from the convalescent camp and from the sick beds at home gradually reinforced this handful of devoted men. Nevertheless, it failed to reach the strength and proportions of anything like an effective regiment.

“These facts I represented as clearly and forcibly as it was in my power to do, in a memorial to the Secretary of War; in which memorandum I prayed that a brigade which had rendered such service, and incurred such distressing losses, should be temporarily relieved from duty in the field, so as to give it time and opportunity in some measure to renew itself.

“The memorial was in vain. It never even was acknowledged. The depression caused by this ungenerous and inconsiderate treatment of a gallant remnant of a brigade that had never once failed to do its duty most liberally and heroically, almost unfitted me to remain in command. True, however, to those who had been true to me – true to a position which I considered sacred under the circumstances – I remained with what was left of my brigade; and though feeling that it was to a sacrifice rather than to a victory that we were going, I accompanied them and led them through all the operations required of them at Scott’s Mills and Chancellorsville beyond the Rappahannock.

“A mere handful of my command did its duty at those positions with a fidelity and resolution which won for it the admiration of the army. It would be my greatest happiness, as it would surely be my highest honour, to remain in the companionship and charge of such men; but to do so any longer would be to perpetuate a public deception, in which the hard-won honours of good soldiers, and in them the military reputation of a brave old race, would inevitably be involved and compromised. I cannot be a party to this wrong. My heart, my conscience, my pride, and all that is truthful, manful, sincere and just within me forbid it.

“In tendering my resignation, however, as the Brigadier General in command of this poor vestige and relic of the Irish Brigade, I beg sincerely to assure you that my services, in any capacity that can prove useful, are freely at the summons and disposition of the Government of the United States. That Government, and the cause, and the liberty, the noble memories, and the future it represents, are entitled, unquestionably and unequivocally, to the life of every citizen who has sworn allegiance to it, and partaken of its grand protection. But while I offer my own life to sustain this good Government, I feel it my first duty to do nothing that will wantonly imperil the lives of others, or, what would be still more grievous and irreparable, inflict sorrow and humiliation upon a race, who, having lost almost everything else, find in their character for courage and loyalty an invaluable gift, which, I, for one, will not be so vain and selfish as to endanger.

“I have the honour to be most respectfully and truly yours,

“Thomas Francis Meagher, Brigadier General Commanding,” (Paul pg 131 & 132).

Brig Gen Thomas Francis Meagher, 1st commander of the Irish Brigade

QUOTES

The visiting Spanish General Juan Prim said, “I don’t wonder the Irish fight so well; their cheers are as good as the bullets of other men,” (Bilby pg 41).

“During Lincoln’s visit to the army {after the battle of Malvern Hill}, 1st Lt James M Birmingham, adjutant of the 88th New York, emerged from a swim in the James. With his wet underwear drying on his body, the Lieutenant walked over to the 69th camp to visit his brother. When Birmingham turned a corner and saw the President and Generals McClellan and Sumner speaking with Colonel Nugent, he ducked behind some cover and eavesdropped on the conversation. Forever after the 88th’s adjutant would remember that he saw Lincoln, impressed by the Irish Brigade’s sacrifices, lift a corner of the 69th’s flag ‘and kissed it, exclaiming, “God bless the Irish flag.” (Bilby pg 49).

General George Pickett wrote to his fiancée, “Your soldier’s heart almost stood still as he watched those sons of Erin fearlessly rush to their deaths. The brilliant assault on Marye’s Heights of their Irish brigade was beyond description. We forgot they were fighting us and cheer after cheer at their fearlessness went up all along our lines!”, (Brooks pg 158).

After the battle of Antietam, some of the officers of the Irish Brigade went to see the mortally wounded General Richardson, who told the officers, “I placed your brigade on the ground you occupied because it was necessary to hold it, and I knew that you would hold it against all odds, and once you were there, I had no further anxiety in regard to the position,” (Corby pg 373).

A correspondent from the London Times who witnessed the battle of Fredericksburg, wrote back to London describing the assault of the Irish Brigade. Praise from a newspaper which was hardly pro-Irish magnifies the deeds of the men on that December day. “To the Irish division, commanded by General Meagher, was principally committed to the desperate task of bursting out of the town of Fredericksburg, and forming, under the withering fire of the Confederate batteries, to-attack Marye’s Heights, towering immediately in their front. Never at Fontenoy, Albuera, or at Waterloo, was more undaunted courage displayed by the sons of Erin than during those six frantic dashes which they directed against the almost impregnable position of their foe…After witnessing the gallantry and devotion exhibited by these troops, and viewing the hill-sides for acres strewn with their Corpsses thick as autumnal leaves, the spectator can remember nothing but their desperate courage, and regret that it was not exhibited in a holier cause. That any mortal men could have carried the position before which they were wantonly sacrificed, defended as it was, it seems to me idle for a moment to believe. But the bodies which lie in dense masses within forty yards of the muzzles of Colonel Walton’s guns are the best evidence what manner of men they were who pressed on to death with the dauntlessness of a race which has gained glory on a thousand battlefields, and never more richly deserved it than at the foot of Marye’s Heights on the 13th day of December – 1863,” (Coyngham Chapter 16).

Describing the carnage after the battle of Fredericksburg, Col. Heros Von Borcke, who was the chief of staff to Gen JEB Stewart, stated that, “More than twelve hundred bodies were found on the small plain between Mary’s Heights and Fredericksburg. The greater part of these belonged to Meagher’s brave Irish Brigade which was nearly annihilated during the several attacks,” (Corby pg 378).

At the battle of Chancellorsville before the Irish Brigade was called into action a nervous recruit asked, “What are we going in here for?”

“Sure, we’ll be after making a little history,” said the veteran, (Jones pg 130).

After the battle of the Wilderness Major General Winfield Scott Hancock mentioned the Irish Brigade in his dispatches, “The Irish Brigade, commanded by Colonel Thomas Smyth…attacked the enemy vigorously on his right and drive the line some distance. The Irish Brigade was heavily engaged, and although four-fifths of its members were recruits, it behaved with great steadiness and gallantry, losing largely in killed and wounded,” (Paul pg 168).

At the 4th anniversary of the forming of the Irish Brigade, a celebration was held at Ream’s Station where Brigadier General Meagher said, “Every battlefield, from Bull Run to Ream’s Station, added another laurel to the wreath which the war would transfer them to posterity,” (Bilby pg 119).

General Miles stated that, “{I bear} testimony to the unflinching bravery of the Irish troops on all occasions,” (Bilby pg 119).

“A large body of infantry advance around our right and take up position in an open field. While we were wondering what troops they were, a breeze blew open and the folds of a flag and we saw the green flag of Ireland. Then we knew it was Meagher’s fighting Irish brigade, and we felt that not a man in the brigade would yield while life lasted, and where that green flag would lead it would be followed by every true son of Erin, even to the very jaws of death.” From the regimental history of the 63rd Pennsylvania, 1st Division, III Corps, Army of the Potomac, which was in retreat from the Peninsula, March 1862, (Pritchard pg 56).

At a recruiting rally in New York City at the Seventh Armoury during the summer of 1862, Meagher told the crowd, “The Irish Brigade in the way of marching did no more than this [French’s] brigade did; nor did it do any more duty in the trenches or on picket than the brigades of Caldwell and Sickles; nor was it more exposed to the unhealthiness of the climate – to the dampness, to the miasma, to the drenching rain, or the deadening sun of the foul lowlands in front of Richmond – than any other brigade along the line.

“Ah! But it did more fighting and it is that which reduced its ranks. Well, whose fault is that? If Irishmen had not long ago established for themselves a reputation for fighting, which a consummate address and a superlative ability; if it had not long ago been accepted, as a gospel truth, that Galway beats Bannagher, and Bannagher beats the devil; and if the boys of the Irish Brigade had not, with an untoward innocence, shown themselves, the first chance they had, as trustworthy as their blessed old sires, and just as eager and ravenous for a fight as that magnificent old heathen from Connaught, the last unbaptised monarch of Ireland, who ran wild about Europe, daring every son of a Goth or Frank to tread on his coat-tails until he came slap up against the Alps, where he went off in a flash; if it was not for this, you may depend on it, the Irish Brigade would not have had any more fighting to do than any one else…

“Heroic old Sumner would never have asked us, as he rode along the front, “Are the Green Flags ready?” Nor would the gallant Fitz-John Porter have kindled into rapture, has he did on Malvern Hill, as the Irish hurrah came sweeping through the flame and roar of the battle from the rear…Nor would General McClellan, the indomitable young chief and glory of the Army of the Potomac, have thanked the soldiers of the Irish Brigade, as he did on the 4th of July, for “their superb conduct in the field” – those are the very words he used; nor would he have expressed the wish, as he ardently did on the same occasion, that he had twenty thousand more of them.

“Come, my countrymen, one more effort, magnanimous and chivalrous, for the Republic, which to thousands and thousands and hundreds of thousands of you has been a shelter, a home, a tower of impregnable security, a pedestal of renown and a palace of prosperity, after the worrying, the scandals and the shipwreck that, for the most part have been for many generations the implacable destiny of our race. Come, my countrymen, in the name of Richard Montgomery, who died to assert the liberty, and in the name of Andrew Jackson, who swore by the Eternal to uphold the authority of the nation. As you exult in the gallantry of James Shields – and as you point with the highest pride to the staunch loyalty, the patient courage, and stern nerve of Michael Corcoran…follow me to the James River and there cast your fortunes with that Brigade which, to the credit and glory of Ireland, has already on seven battlefields proved its devotion to the republic,” (Jones Pg 100 & 101).

As the Irish Brigade watched the Confederates strengthen their position before Fredericksburg in December 1862, one soldier said to Father Corby, “Father, are they going to lead us in front of those guns which we have seen them placing unhindered, for the past three weeks?” Corby replied, “Do not trouble yourself; your generals know better than that,” (Pritchard pg 66).

Thomas F Galway, who was in French’s Division, who would later become the associate editor of the ‘Catholic World’ and a professor at Manhattan College wrote about the Irish Brigade at Fredericksburg, in his diary. “Line after line of our men advance in magnificent order out from the city towards us. But none of them pass the position which we took at our first dash and which we have continued to hold until now, in spite of the concentrated fire of the enemy’s batteries, and the destructive fusillade of his infantry.

“There is one exception, the Irish Brigade, which comes out from the city in glorious style, their green sunbursts waving, as they have waved on many a bloody battlefield before, in the thickest of the fight where the grim and thankless butchery of war is done. Every man has a sprig of green in his cap, and a half-laughing, half-murderous look in his eye. They pass just to our left, poor fellows, poor glorious fellows, shaking goodbye to us with their hats! They reach a point within a stone’s throw of the stonewall. No farther. They try to go beyond, but are slaughtered. Nothing could advance further and live. They lie down doggedly, determined to hold the ground they have already taken. There, away out in the fields to the front and left of us, we see them for an hour or so, lying in line close to that terrible stone wall,” (Jones pg 116).

At the end of March 1863 Sergeant Peter Welsh, the color-bearer of the 28th Massachusetts after the 17th March 1863, wrote to his wife about her perceptions of the dangers of battle… “And if you think the colors were aimed at by the enemy I would be in the full more danger in any other part of the company then carrying the flag there is no such thing as taking shure aim in the battle field the smoke of powder the noise of firearms and cannon and the excittement of the battle field makes it impossible so that the if the colors are fired at those on either side of the colors for the length of the company are more likely to get struck then the color bearer…” (Kohl pg 81).

During the siege of Petersburg, “A truce was declared on the picket line and both sides mingled freely, exchanging newspapers, coffee, tobacco, and whiskey. The Northern and Southern Irishmen argued about the war when they had a chance. “A fine bunch of Irishmen you are, coming into the South and burning our farms and acting worse than the English ever did in Ireland,” said one of Mahone’s Irish immigrant Confederates after he had been captured by a group of soldiers from the 69th New York.

“ “Ah, hold yer whict,” replied one of the New York Irishmen. “A fine bunch of Irishmen you are, trying to break up the Union that gave ye a home and fighting for the rich slave owners,” (Seagrave pg 92).

William F Fox in his works “Regimental Losses In The American Civil War, 1861-1865,” stated that the Irish Brigade was, “Perhaps the best known of any brigade organization, it having made an unusual reputation for dash and gallantry. The remarkable precision of its evolutions under fire, its desperate attack on the impregnable wall at Marye’s Heights; its never failing promptness on every field; and its long continuous service, made for it a name inseparable from the history of the war.”

COMMANDING OFFICERS OF THE IRISH BRIGADE

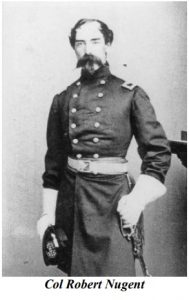

Thomas Francis Meagher (left), Robert Nugent (right)

BRIG GENERAL T.F. MEAGHER – 13th March 1862 to 28th June 1862

COLONEL ROBERT NUGENT – 28th June 1862 to 29th June 1862

BRIG GENERAL T.F. MEAGHER – 29th June 1862 to 16th July 1862

COLONEL ROBERT NUGENT – 16th July 1862 to 8th August 1862

BRIG GENERAL T.F. MEAGHER – 8th August 1862 to 17th September 1862

COLONEL JOHN BURKE – 17th September 1862 to 18th September 1862

BRIG GENERAL T.F. MEAGHER – 18th September 1862 to 20th December 1862

COLONEL PATRICK KELLY – 20th December 1862 to 18th February 1863

BRIG GENERAL T.F. MEAGHER – 18th February 1863 to 8th May 1863 (Meagher was absent from command 24th March 1863 to 26th April 1863 in Philadelphia Pennsylvania, and New York, for treatment of a severe attack of rheumatism. He resigned his commission on 5th May 1863).

COLONEL PATRICK KELLY – 8th May 1863 to 12th January 1864

COLONEL RICHARD BYRNES – 12th January 1864 to 14th February 1864

MAJOR A.J. LAWLER – 14th February 1864 to 25th March 1864

COLONEL T.A. SMYTH – 25th March 1864 to 17th May 1864

COLONEL RICHARD BYRNES – 17th May 1864 to 3rd June 1864 (Byrnes was wounded in action).

COLONEL PATRICK KELLY – 3rd June 1864 to 16th June 1864 (Kelly was killed in action at Petersburg, Virginia).

COLONEL RICHARD BYRNES – 16th June 1864 to 28th June 1864

On the 27th June 1864, the 2nd Brigade (Irish Brigade) of the 1st Division of the 2nd Corps of the Army of the Potomac was consolidated with the 3rd Brigade, and was essentially no longer an independent command. The 69th, 88th and 63rd New York regiments stayed together under the command of Major Moroney, as the 28th Massachusetts, and 116th Pennsylvania were transferred to other divisions. By November 1864 the New York regiments received an influx of new recruits and were reorganised again into a separate command, and the 28th Massachusetts joined them soon after.

LT. COLONEL D.F. BURKE – 2nd November 1864 to 5th November 1864

COLONEL ROBERT NUGENT – 5th November 1864 to 29th January 1865

COLONEL R.C. DURYEA – 29th January 1865 to 17th February 1865

COLONEL ROBERT NUGENT – 17th February 1865 to 25th June 1865, the end of the war.

It was fitting that Colonel Robert Nugent, who was with the 69th New York at the very birth of the Irish Brigade, was its commanding officer at the very end.

A SKETCH OF THE OFFICERS OF THE 69TH NEW YORK

GENERAL ROBERT NUGENT – Post-civil war brevet-Colonel and Captain 16th Infantry, U. S. A., formerly major and Lieutenant-Colonel of the 69th New York Volunteers, was a native of Kilkeel, county Down; was in all the battles of the Brigade, except Antietam, when he was absent, sick, until Fredericksburg, when he was wounded by a rifle ball in the groin, his pistol, which was shattered, saving his life; was Acting Assistant Provost-Marshal-General of New York for a considerable period, during which he administered a dangerous and important office with dignity and honour. He commanded the Irish Brigade after General Meagher’s resignation. He was a very dignified commander and an officer of high executive ability and undoubted gallantry.

LIEUTENANT-COLONEL JAMES KELLY – He was also a Captain of the 16th Infantry, U. S. A., was a native of Monaghan; was with the regiment up to the battle of Antietam, when he commanded and led the 69th in their famous charge. Here he received two wounds in the face and shoulder. On the consolidation of the regiment, June, 1863, he was ordered to join his regiment in the regular army, and was subsequently in command of the recruiting depot at Grand Rapids, Michigan, from which at this post he was transferred to his old command as Lieutenant Colonel. He then commanded the Brigade for a short period, at the end of which he rejoined his regular command, and served with renewed distinction and popularity under Sherman in his famous campaigns. No braver or more efficient officer could be found in the service.

LIEUTENANT-COLONEL JAMES E. McGEE – He succeeded Colonel Kelly, and commanded two brigades of the First Division, Second Corps, for a considerable period during the most active preliminary movements of Grant’s campaign, until he was honourably discharged after three years’ service, and on account of wounds received at Petersburg, Virginia, June 16, 1864. Colonel McGee was born in 1830, near the village of Cushendall, in the county of Antrim, Ireland; and was educated at St. Peter’s College. Between 1847 and 1848, he was sub-editor of the “Nation”, and secretary of a Confederate club. After the failure of the Young Ireland movement he emigrated to the United States, and was for several years connected with the Irish American Press. He finally joined the volunteer service of the United States; commanded Company F, 69th until 1865, when, after reorganizing the regiment, he was commissioned Lieutenant Colonel. Colonel McGee was very popular in the army, on account of his agreeable, social, manly demeanour; for gallantry and great executive ability and military tact, he had few superiors.

LIEUTENANT-COLONEL JAMES J. SMITH – He was for a long period the adjutant of the ” Old Sixty-ninth,” entered into active service with that command in the early months of the rebellion. He was with the Brigade in that capacity in every engagement, except Fredericksburg, when he was absent, detailed on recruiting service. Colonel Smith was a fine executive officer, and remarkable for coolness, intrepidity, and almost excessive modesty. He was promoted Lieutenant-Colonel, February 16th, 1865. He was a native of Monaghan.

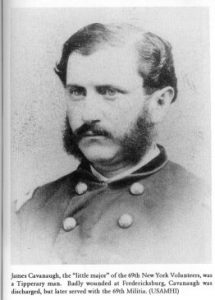

MAJOR JAMES CAVANAGH – He was popularly known as ” the little Major;’ he was a native of Tipperary, and a gallant soldier. He was severely wounded at Fredericksburg, and was obliged to resign after that disastrous battle.

MAJOR JOHN GARRET – comes next on the roster. He, Coyningham believes, was born in Ireland, served in the Mexican war, and then in the 15th New York Volunteers, under J. McLeod Murphy, as Captain of a company. He was wounded in the shoulder at Cold Harbor.

SURGEON J. PASCAL SMITH – resigned from ill health.

ASSISTANT-SURGEON HURLEY – was unhappily killed by a fall from his horse. He was a very able, popular officer, and universally regretted.

ASSISTANT-SURGEON REED – a gentlemanly medical practitioner of New York.

SURGEON WILLIAM O’MEAGHER – a native of Killenaule, county Tipperary. He first joined the gallant 37th New York as surgeon, in which he distinguished himself by his coolness in action, his unwearied attention to his patients, and his affable, gentlemanly demeanour. He subsequently joined the 69th New York Volunteers as surgeon, and became popular in the Brigade, both as a clever surgeon and polished gentleman. The doctor was frequently under fire, and on three occasions a prisoner, but was immediately released. He was principally engaged as operator, brigade surgeon, or in charge of hospitals.

DR. JAMES PURCELL – (whose father, Dr. Purcell, of Henry-street, New York-a native of Carrick-on-Suir, Tipperary-had to emigrate to this country on account of his connection with the ’48 business), was born in Ireland, and after taking out his diploma, joined the Irish Brigade as assistant-surgeon, with which he served all through the war. He was a great favourite, and a young man of much promise in his profession.

ASSISTANT-SURGEON CROSBY – Was a native of New York State, was obliged to resign from ill health.

CHAPLAIN – THE REV. THOMAS OUELLET – Was a native of Lower Canada; a most zealous and indefatigable priest, universally respected.

Father Thomas Oullet (post war image)

QUARTERMASTER RICHARD MAYBURY – Was a native of Brooklyn, graduated from the ranks. An intelligent and energetic officer.

MAJOR RICHARD MORONY – He served in the First New York Volunteers during the Mexican war, then in the old 69th next as 1st Lieutenant in the new 69th, promoted Captain and finally Major. He was a brave, active, and efficient officer; witty, genial, and a universal favourite. Mustered out with the regiment. He was a native of New York State.

Major Richard Morony

CAPTAIN B. S. O’NEILL – He left Ireland for the purpose of joining the Brigade, and very early distinguished himself by bravery and gentlemanly conduct; was promoted from the ranks, step by step, until at times he commanded the regiment. He was killed in front of Petersburg, June 16th, 1864.

CAPTAIN R. H. MILLIKEN – Was born in Newburg, New York, of Irish parents, served in the Ninth New York Militia,. A brave, prompt, and careful officer, always ready for duty. He was severely wounded at Cold Harbor, June 3, 1864, from which he recovered with a slight lameness.

LIEUTENANT WILLIAM O’DONOHUE – entered the service as Sergeant Company K (Meagher’s Zouaves); taken prisoner with Corcoran at Bull Run; escaped from Richmond, and enlisted with the 4th United States Artillery; rose to rank of Lieutenant, and was killed at Chancellorsville.

CAPTAIN D. S. SHANLEY – He was formerly Lieutenant in the Chicago Shields Guard, which, under the gallant Mulligan, took a distinguished part in the famous siege of Lexington. After being exchanged, he joined General Meagher, as Captain in the 69th, amongst whose officers he was beloved, and served in every hard-fought battle in which the green flag was borne against the enemy. He was wounded at the battle of Malvern Hill, but had again taken command of his company before the evacuation of Harrison’s Landing. He was a thoroughly brave young officer, of the most cheerful disposition and unblemished reputation, who would feel a stain deeper than a wound. He fell at Antietam, while bravely leading on his company. His remains were interred in the Catholic Cemetery at Frederick.

CAPTAIN FELIX DUFFY – commanding Company G, 69th, was a brave and experienced officer, and had already served his adopted country in the Mexican war, receiving the strongest marks of approbation from his commanding officers. He was for many years connected with the First Division of New York State Militia, and for some time before the breaking out of the rebellion held the post of Captain of Co. G., 69th Regiment N. Y. S. M., which Corps he accompanied to the defence of the National Capitol in 1861. He transferred to the 69th New York State Volunteers on its formation. He was killed at Antietam.

LIEUT. JASON E. BYRNE – a native of Clonmel, Co. Tipperary, was educated for the priesthood, emigrated and joined the Brigade, and bravely served until he fell at Cold Harbor.

LIEUTENANT R. A. KELLY – was a native of Athy Co Kildare, Ireland, and was a splendid specimen of manhood, being, though only twenty-one years of age, fully six feet three inches in height. A soldier, almost by instinct, he accompanied the Sixty-ninth Regiment, under Colonel Corcoran, to Virginia at the outbreak of the rebellion, and at the first battle of Bull Run was wounded in the right hand. When the Irish Brigade was commenced, he at once joined its ranks, and served with his regiment all through the desperate struggles in which it has borne so distinguished a part. No braver man has given his life for the cause of the Union, or no better soldier fell on the bloody plain of Antietam.

SECOND-LIEUTENANT LUKE BRENNAN – He promoted from the ranks.

CAPTAIN Wm. BENSON – (Company E), resigned.

FIRST-LIEUTENANT CHARLES M. LUCKY – No information available.

SECOND-LIEUTENANT PETER CONLON – No information available.

SECOND-LIEUTENANT MICHAEL J. BRENNAN – He was promoted from the ranks; received four wounds at Fredericksburg; resigned in consequence. Had service later in Veteran Reserve Corps.

SECOND-LIEUTENANT JOSEPH M. BURNS – He was a native of Scotland, of Irish descent, wounded at White Oak Swamp. Later an officer in the navy.

FIRST-LIEUTENANT PATRICK BUCKLEY – He was promoted from the ranks. Killed at Fredericksburg.

FIRST-LIEUTENANT PATRICK J. KELLY – Killed on the field at Antietam.

SECOND-LIEUTENANT TERENCE DUFFY – He resigned after the battle of Fredericksburg, from disability.

FIRST-LIEUTENANT PATRICK CALLAHAN – He was promoted from the ranks. Served twenty-three years in the U. S. regular army; wounded at Fredericksburg in four places. He later had service as an officer in Veteran Reserve Corps.

SECOND-LIEUTENANT DAVID BURKE – promoted from the ranks of Captain McGee’s company; wounded at Fredericksburg. Mustered out on the consolidation of regiment.

CAPTAIN JAMES LOWRY – (Company H), resigned from ill health.

FIRST-LIEUTENANT PHILIP CARR – He was wounded at Malvern Hill. Resigned from disability.

CAPTAIN JOHN T. TOAL – He was wounded at Fredericksburg. Resigned in consequence. Was successively promoted to 1st Lieutenant and Captain for distinguished service.

FIRST-LIEUTENANT JOHN D. MULHALL – He was formerly a 1st Lieutenant in the Brigade of St. Patrick, in the Papal service. Distinguished himself in Lamoriciere’s campaign against the French, and received the medal of St. Peter and two other decorations.

SECOND-LIEUTENANT PATRICK CARNEY – He was promoted from the ranks. Received nine wounds at the battle of Fredericksburg, from the effects of which he was obliged to resign. Later had service in the Veteran Reserve Corps.

CAPTAIN THOMAS SCANLAN – He resigned from ill health.

FIRST-LIEUTENANT PATRICK MORRIS – No information available.

SECOND-LIEUTENANT JAMES COLLINS – He was promoted from the ranks of Captain McGee’s company. Wounded at Fredericksburg.

CAPTAIN JAMES McMAHON – He was formerly on General Meagher’s and General Richardson’s staffs, then Colonel of the 164th N. Y. Vols. Killed at Cold Harbor, June 5th, 1864.

FIRST-LIEUTENANT JOHN CONWAY – He was killed at Antietam.

SECOND-LIEUTENANT PETER KELLY – He was wounded at the first battle of Bull Run, taken prisoner, and escaped from Richmond; resigned.

CAPTAIN LYNCH – He was a native of the town of Limerick, joined the 69th as private, and soon rose to a captaincy. He was captured twice, and was a good and faithful officer. Colour-bearer Henry Croker, who gallantly carried the colours of his regiment at Cold Harbor, belonged to his company.

CAPTAIN M. H. MURPHY – Co. A, also graduated from the ranks; was severely wounded in front of Petersburg. A brave, intelligent, soldierly officer, and a native of Tipperary.

LIEUTENANT R. H. MURPHY – He originally belonged to the Corcoran Legion, in which he served with credit until commissioned in the 69th. He was mortally wounded at Amelia Springs, and died subsequently in hospital.

CAPTAIN DAVID LYNCH – He was a thorough soldier and excellent officer, was promoted from the ranks, having served throughout the war. Was severely wounded at Fredericksburg, transferred to the Veteran Corps, but again returned to his old command at his own request; was taken prisoner at Reams’ Station, exchanged, and then promoted to a Captain.

CAPTAIN HARRY MCQUADE – He graduated from the ranks; was severely wounded at Deep Bottom, taken prisoner at Reams’ Station, exchanged, and then promoted to a Captain.

LIEUTENANT JOHN NUGENT – He served with Corcoran; re-enlisted in the new regiment, was promoted from the ranks for bravery and good conduct.

LIEUTENANT JOHN MEAGHER – He entered the service August, 1862, promoted sergeant, then lieutenant. He was wounded severely on two or three occasions.

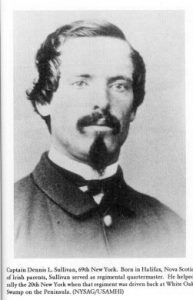

QUARTERMASTER DENIS SULLIVAN – Was a native of Halifax, Nova Scotia, of Irish parentage. He was always with the regiment, and was instrumental in rallying the 20th N. Y. V. when panic-stricken at White Oak Swamp. Mustered out at expiration of term of service.

CAPTAIN JAMES SAUNDERS – (Company A), native of Cavan; in every action with his regiment except Chancellorsville. Mustered out on consolidation of service.

FIRST-LIEUTENANT ANDREW BIRMINGHAM – He died of wounds received at Fredericksburg, December, 1862.

FIRST-LIEUTENANT THOMAS REYNOLDS – He was killed at Malvern Hill, July 1st, 1862.

CAPTAIN RICHARD A. KELLY – He was promoted from the ranks for distinguished bravery at Malvern Hill, having personally taken prisoner the Lieutenant-Colonel of the 10th Louisiana Vols, and two others. Mustered out on the consolidation of the regiment; afterwards commissioned as Captain of Company A, on the reorganization of regiment, and died of wounds received at Spotsylvania, May, 1864, while a prisoner in the hands of the enemy.

CAPTAIN LEDDY – (Company B), wounded dangerously at Malvern Hill and Fredericksburg. Later had service in Veteran Reserve Corps.

LIEUTENANT M. LEDDY – a brother of the above. He was promoted from the ranks for bravery and long service. He was wounded on two or three occasions.

FIRST-LIEUTENANT LAURENCE CAHILL – He was wounded badly at Malvern Hill, and obliged to resign in consequence. Later had service in Veteran Reserve Corps.

JOHN J. GOSSON – Captain Company C, 69th N. Y. S. M., and First A. D. C. Staff of General Meagher; was with him in the above capacity in all the battles of the Irish Brigade. Son of J. Gosson, Esq., formerly of Swords, county Dublin. Entered the Austrian service through the influence of Daniel O’Connell, and served under his friend, General Count Nugent, as Lieutenant, in Syria, and subsequently, through the introduction of the Count, joined the Seventh Hussars of Austria (Prince Reuss’ Hussars), a Hungarian regiment, commanded by Prince Frederick Liechtenstein.

SECOND-LIEUTENANT ROBERT LAFFAN – He lost his arm at Antietam, September 17th, 1862. Promoted from Captain McGee’s company for gallant service. Later he had service in Veteran Reserve Corps.

CAPTAIN JASPER WHITTY – (Company C), wounded at the first battle of Bull Run while with the 69th N. Y. S. M. ; lost an eye at White Oak Swamp, and was wounded at Antietam. In consequence obliged to resign.

FIRST-LIEUTENANT NAGLE – (a descendant of the celebrated Edmund Burke, who was a cousin of his German grandfather)-wounded seriously at Antietam, in the right shoulder. He was later made a Captain. Later had service in Veteran Reserve Corps.

SECOND-LIEUTENANT CHARLES WILLIAMS – He was killed on the field at Antietam.

CAPTAIN MAURICE W. WALL – He was a native of Tipperary; entered the service in the old Sixty-ninth, Co. K ; was next commissioned in the 88th . He was an excellent staff officer, being equally brave, reliable, and intelligent.

CAPTAIN TIMOTHY L. SHANLEY – He fought with Mulligan at Lexington, Missouri, afterwards joined the 69th with his company. Died in Frederick City, Maryland. October 2nd, in consequence of wounds received at Antietam.

CAPTAIN JOHN H. DONOVAN – He lost an eye at Malvern Hill, July 1st, 1862. He was later a Major in the Veteran Reserve Corps.

SECOND-LIEUTENANT MARTIN SCULLY – He was wounded at Fredericksburg, December 13th, 1862 ; also with Mulligan at Lexington.

CAPTAIN MURTHA MURPHY – Company C, a native of gallant Wexford, graduated from the ranks of the old Sixty-ninth. He was in twenty-eight or thirty engagements; was wounded only twice. His last achievement was the capture of thirteen rebels, including an officer, in front of Petersburg, by a little personal strategy worthy of note, for which he should have received the compliment of a general order, and at least a brevet appointment. But our gallant friend was too modest, and such acts were not very uncommon in the command.

CAPTAIN JOHN C. FOLEY – Was a native of Tipperary. He entered the 88th NYSV as 1st Lieutenant at the formation of the Irish Brigade. He afterwards raised a company and joined the 69th NYSV and acted as Assistant Acting Adjutant General. He was wounded at Mine Run. He was mustered out at the end of the war.

CAPTAIN MAURICE W. WALL – Mustered out of the 88th NYSV on consolidation of the regiment, he then joined the 69th NYSV as a Captain on its veteran enlistment. He served until the end of the war. He was a native of Tipperary, who entered the army in Meagher’s Zouaves Co K 69th NYSM. He was a staff officer who was considered brave, reliable and intelligent.

CAPTAIN EDWARD F. O’CONNOR – He was a fine, intelligent young officer, who also sprang from the ranks through merit and bravery; was wounded at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania; taken prisoner at Reams’ Station; exchanged, and then promoted captain Company F.

ADJUTANT DANIEL DOLAN – He was a native of Tipperary; was originally hospital steward, in which position he showed unusual tact, discretion, and capacity; but being ambitious he was promoted into the line, and then to the staff. In this position, for which be was very well fitted, he acquitted himself with distinction, and maintained the previous character of the regiment for order and discipline. He was in almost every engagement with the regiment.

LIEUTENANT JOHN NUGENT – He graduated from the ranks of the old 69th, taken prisoner at Bull Run and released; he then joined the new regiment; was wounded at the battle of Fredericksburg; participated in all the other battles of the Brigade up to the end of the war. He was a good, reliable officer.

LIEUTENANT JAMES MCCANN – He was promoted from the ranks. A steady, reliable officer.

LIEUTENANT OWEN MCNULTY – He was also from the ranks. A good disciplinarian.

LIEUTENANT PATRICK WARD – He was also from the ranks. A steady, well-conducted officer.

LIEUTENANT JAMES CONWAY – He was a good soldier and officer, promoted from the ranks.

LIEUTENANT GEORGE M. BELDING – He was a native of New York State, Served in the 32nd New York Volunteers, then in the 6th Cavalry, from which he was promoted to the 69th New York, in which he was quite a favourite, by his gentlemanly conduct and rigid performance of duty.

LIEUTENANT TERENCE SCANLON – He was a graduate of the old 69th; was wounded at the battle of Malvern Hill; taken prisoner and released; promoted from the ranks for good conduct, long and gallant services.

LIEUTENANT THOMAS MCGRATH – He was with the Brigade from its first organization; wounded at Gettysburg; taken prisoner at Reams’ Station; released, and promoted for gallant services.

LIEUTENANT GEORGE NEVINS – He was promoted from the ranks. An intelligent, brave soldier.

LIEUTENANT ROBERT MCKINLEY – He was a native of Scotland; served three months in the 79th New York, also in the 1st New York Cavalry; promoted from the ranks of the 69th for bravery and good conduct; was taken prisoner before Petersburg.

LIEUTENANT WILLIAM HERBERT – He was also promoted from the ranks; was in every battle with the regiment.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Irish Green And Union Blue – The Civil War Letters Of Peter Welsh” – Edited by Lawrence Frederick Kohl with Margaret Cosse Richard. (Fordham University Press, New York, 1986).

“Kelly’s Heroes – The Irish Brigade At Gettysburg” – T L Murphy (Farnsworth House Military Impressions 1997).

“Memoirs Of Chaplain Life – Three Years With The Irish Brigade In The Army Of The Potomac” – William Corby CSC, edited by Lawrence Frederick Kohl ( Fordham University Press, New York, 1992).

“Never Were men So Brave – The Irish Brigade During The Civil War” – Susan Provost Beller (Margaret K McKelebrerry Books 1998).

“The 69th New York & Other Regiments Of The Irish Brigade” (1866) – Captain D P Conyngham.

“The Blue & The Gray” – By Henry Steele-Commager (Fairfax Press 1982).

“The Fredericksburg Campaign” – V Brooks (Combined Publishing, Pennsylvania, 2000).

“The Irish Brigade” – Paul Jones (New English Library 1971).

“The Irish Brigade – A Pictorial History Of The Famed Civil War Fighters” – Russ A Pritchard Jr (Courage Books 2004).

“The Irish Brigade In The Civil War” – J G Bilby (Combined Publishing, Pennsylvania, 1998).

“Winfield Scott Hancock – A Soldier’s Life” – by David M Jordan (Indiana University Press 1996).