(this page is currently being updated)

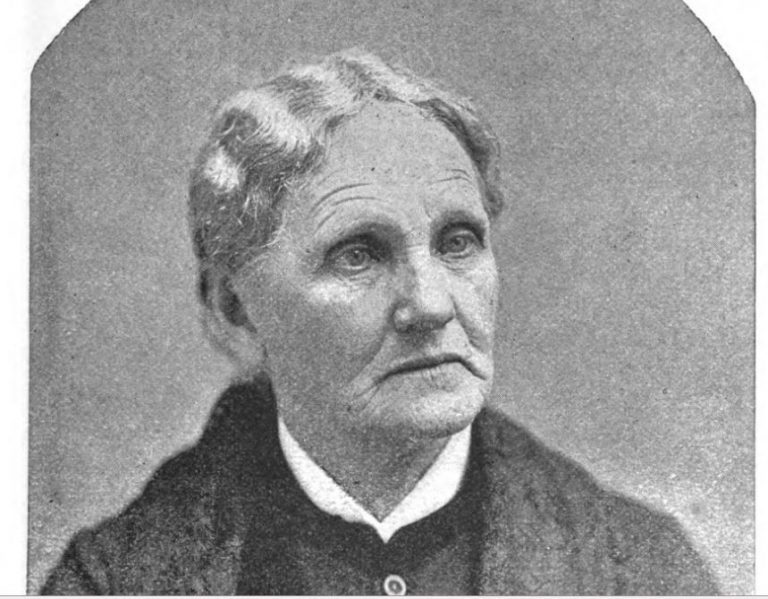

HARRIET TUBMAN

Harriet Tubman (born Araminta Ross, c. March 1822 – March 10, 1913) was an American abolitionist and social activist. After escaping slavery, Tubman made some 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 enslaved people, including her family and friends, using the network of antislavery activists and safe houses known collectively as the Underground Railroad. During the American Civil War, she served as an armed scout and spy for the Union Army. In her later years, Tubman was an activist in the movement for women’s suffrage.

Born into slavery in Dorchester County, Maryland, Tubman was beaten and whipped by enslavers as a child. Early in life, she suffered a traumatic head wound when an irate overseer threw a heavy metal weight, intending to hit another slave, but hit her instead. The injury caused dizziness, pain, and spells of hypersomnia, which occurred throughout her life. After her injury, Tubman began experiencing strange visions and vivid dreams, which she ascribed to premonitions from God. These experiences, combined with her Methodist upbringing, led her to become devoutly religious.

In 1849, Tubman escaped to Philadelphia, only to return to Maryland to rescue her family soon after. Slowly, one group at a time, she brought relatives with her out of the state, and eventually guided dozens of other enslaved people to freedom. Tubman (or “Moses”, as she was called) travelled by night and in extreme secrecy, and later said she “never lost a passenger”. After the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed, she helped guide escapees farther north into British North America (Canada), and helped newly freed people find work. Tubman met John Brown in 1858, and helped him plan and recruit supporters for his 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry.

When the Civil War began, Tubman worked for the Union Army, first as a cook and nurse, and then as an armed scout and spy. For her guidance of the raid at Combahee Ferry, which liberated more than 700 enslaved people, she is widely credited as the first woman to lead an armed military operation in the United States. After the war, she retired to the family home on property she had purchased in 1859 in Auburn, New York, where she cared for her aging parents. She was active in the women’s suffrage movement until illness overtook her and was admitted to a home for elderly African Americans, which she helped establish years earlier. Tubman is commonly viewed as an icon of courage and freedom.

American Civil War

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Tubman had a vision that the war would soon lead to the abolition of slavery. More immediately, enslaved people near Union positions began escaping in large numbers. General Benjamin Butler declared these escapees to be “contraband” – property seized by northern forces – and put them to work, initially without pay, at Fort Monroe in Virginia. The number of “contrabands” encamped at Fort Monroe and other Union positions rapidly increased. In January 1862, Tubman volunteered to support the Union cause and began helping refugees in the camps, particularly in Port Royal, South Carolina

In South Carolina, Tubman met General David Hunter, a strong supporter of abolition. He declared all of the “contrabands” in the Port Royal district free, and began gathering formerly enslaved people for a regiment of black soldiers. U.S. President Abraham Lincoln was not yet prepared to enforce emancipation on the southern states and reprimanded Hunter for his actions. Tubman condemned Lincoln’s response and his general unwillingness to consider ending slavery in the U.S., for both moral and practical reasons:

God won’t let master Lincoln beat the South till he does the right thing. Master Lincoln, he’s a great man, and I am a poor negro; but the negro can tell master Lincoln how to save the money and the young men. He can do it by setting the negro free.

Tubman served as a nurse in Port Royal, preparing remedies from local plants and aiding soldiers suffering from dysentery and infectious diseases. At first, she received government rations for her work, but to dispel a perception that she was getting special treatment, she gave up her right to these supplies and made money selling pies and root beer, which she made in the evenings.

Scouting and the Combahee River Raid

When Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, Tubman considered it a positive but incomplete step toward the goal of liberating all black people from slavery. She turned her own efforts towards more direct actions to defeat the Confederacy. In early 1863, Tubman used her knowledge of covert travel and subterfuge to lead a band of scouts through the land around Port Royal. Her group, working under the orders of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, mapped the unfamiliar terrain and reconnoitered its inhabitants. She later worked alongside Colonel James Montgomery, and provided him with key intelligence that aided in the capture of Jacksonville, Florida, gathering played a key role in the raid at Combahee Ferry. She guided three steamboats with black soldiers under Montgomery’s command past mines on the Combahee River to assault several plantations. Once ashore, the Union troops set fire to the plantations, destroying infrastructure and seizing thousands of dollars worth of food and supplies. Forewarned of the raid by Tubman’s spy network, enslaved people throughout the area heard steamboats’ whistles and understood that they were being liberated. Tubman watched as those fleeing slavery stampeded toward the boats; she later described a scene of chaos with women carrying still-steaming pots of rice, pigs squealing in bags slung over shoulders, and babies hanging around their parents’ necks Armed overseers tried to stop the mass escape, but their efforts were nearly useless in the tumult As Confederate troops raced to the scene, the steamboats took off toward Beaufort with more than 750 formerly enslaved people.

Newspapers heralded Tubman’s “patriotism, sagacity, energy, [and] ability” in the raid, and she was praised for her recruiting efforts – more than 100 of the newly liberated men joined the Union army. Reports about her involvement in the raid led to a revival of the “General Tubman” appellation previously given to her by John Brown. Although her contributions have sometimes been exaggerated, her role in the raid led to her being widely credited as the first woman to lead U.S. troops in an armed assault.

In July 1863, Tubman worked with Colonel Robert Gould Shaw at the assault on Fort Wagner, reportedly serving him his last meal. She later described the battle to historian Albert Bushnell Hart:

And then we saw the lightning, and that was the guns; and then we heard the thunder, and that was the big guns; and then we heard the rain falling, and that was the drops of blood falling; and when we came to get the crops, it was dead men that we reaped.

For two more years, Tubman worked for the Union forces, tending to newly liberated people, scouting into Confederate territory, and nursing wounded soldiers in Virginia, a task she continued for several months after the Confederacy surrendered in April 1865.

CLARA BARTON

Clarissa Harlowe Barton (December 25, 1821 – April 12, 1912) was an American nurse who founded the American Red Cross. She was a hospital nurse in the American Civil War, a teacher, and a patent clerk. Since nursing education was not then very formalized and she did not attend nursing school, she provided self-taught nursing care. Barton is noteworthy for doing humanitarian work and civil rights advocacy at a time before women had the right to vote. She was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1973.

Beginning in 1832, when Barton was ten years old, she acted as a nurse to her brother David for two years after he fell from the roof of a barn and sustained a severe head injury. In nursing her brother, she learned how to deliver prescription medications and perform the practice of bloodletting, in which blood was removed from the patient by leeches attached to the skin. David eventually made a full recovery.

Early professional life

In 1855, she moved to Washington, D.C., and began work as a clerk in the U.S. Patent Office; this was the first time a woman had received a substantial clerkship in the federal government and at a salary equal to a man’s salary. For three years, she received much abuse and slander from male clerks. Subsequently, under political opposition to women working in government offices, her position was reduced to that of copyist, and in 1858, under the administration of James Buchanan, she was fired because of her “Black Republicanism”.After the election of Abraham Lincoln, having lived with relatives and friends in Massachusetts for three years, she returned to the patent office in the autumn of 1860, now as temporary copyist, in the hope she could make way for more women in government service.

American Civil War

On April 19, 1861, the Baltimore Riot resulted in the first bloodshed of the American Civil War. The victims, members of the 6th Massachusetts Militia, were transported after the violence to the unfinished Capitol Building in Washington, D.C., where Barton lived at the time. Wanting to serve her country, Barton went to the railroad station when the victims arrived and nursed 40 men.[13] Barton provided crucial, personal assistance to the men in uniform, many of whom were wounded, hungry and without supplies other than what they carried on their backs. She personally took supplies to the building to help the soldiers.

Barton quickly recognized them, as she had grown up with some of them and even taught some. Barton, along with several other women, personally provided clothing, food, and supplies for the sick and wounded soldiers. She learned how to store and distribute medical supplies and offered emotional support to the soldiers by keeping their spirits high. She would read books to them, write letters to their families for them, talk to them, and support them.

It was on that day that she identified herself with army work and began her efforts towards collecting medical supplies for the Union soldiers. Prior to distributing provisions directly onto the battlefield and gaining further support, Barton used her own living quarters as a storeroom and distributed supplies with the help of a few friends in early 1862, despite opposition in the War Department and among field surgeons. Ladies’ Aid Society helped in sending bandages, food, and clothing that would later be distributed during the Civil War. In August 1862, Barton finally gained permission from Quartermaster Daniel Rucker to work on the front lines. She gained support from other people who believed in her cause. These people became her patrons, her most supportive being Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts.

After the First Battle of Bull Run, Barton placed an ad in a Massachusetts newspaper for supplies; the response was a profound influx of supplies. She worked to distribute stores, clean field hospitals, apply dressings, and serve food to wounded soldiers in close proximity to several battles, including Cedar Mountain, Second Bull Run, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. Barton helped both Union and Confederate soldiers.[16] Supplies were not always readily available though. At the battle of Antietam, for example, Barton used corn-husks in place of bandages. Speaking of her commitment to being a nurse in the war after experiencing battle, Clara would say, “I shall remain here while anyone remains, and do whatever comes to my hand. I may be compelled to face danger, but never fear it, and while our soldiers can stand and fight, I can stand and feed and nurse them.”

In April 1863, Barton accompanied her brother, David, to Port Royal, South Carolina in the Union-occupied Sea Islands after he was appointed as a quartermaster within the Union Navy. Clara Barton resided in the Sea Islands until early 1864. While in South Carolina, she became friends with prominent abolitionist and feminist Frances Dana Barker Gage, who had traveled south to educate formerly enslaved people (see Port Royal Experiment). Barton also became acquainted with Jean Margaret Davenport, an actress from England who was then residing on the Sea Islands with her husband, Union General Frederick W. Lander. Barton provided medical care to the Black soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment following their attack on Fort Wagner. Additionally, she traveled to Morris Island to nurse Union soldiers there, accompanied by a Black woman named Betsey who worked under Barton during her time in the Sea Islands. She quarreled with General Quincy Adams Gillmore after he suddenly ordered her to evacuate her post at Morris Island. Also in the Sea Islands, she became acquainted with a Union officer, Colonel John J. Elwell. Historian Stephen B. Oates claims that Barton and Elwell had a romantic and sexual relationship

In 1864, she was appointed by Union General Benjamin Butler as the “lady in charge” of the hospitals at the front of the Army of the James. Among her more harrowing experiences was an incident in which a bullet tore through the sleeve of her dress without striking her and killed a man to whom she was tending. She was known as the “Florence Nightingale of America”.She was also known as the “Angel of the Battlefield” after she came to the aid of the overwhelmed surgeon on duty following the battle of Cedar Mountain in Northern Virginia in August 1862. She arrived at a field hospital at midnight with a large number of supplies to help the severely wounded soldiers. This naming came from her frequent timely assistance as she served troops at the battles of Fairfax Station, Chantilly, Harpers Ferry, South Mountain, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Charleston, Petersburg and Cold Harbor.

Postwar

After the end of the American Civil War, Barton discovered that thousands of letters from distraught relatives to the War Department were going unanswered because the soldiers they were asking about were buried in unmarked graves. Many of the soldiers were labeled as “missing.” Motivated to do more about the situation, Barton contacted President Lincoln in hopes that she would be allowed to respond officially to the unanswered inquiries. She was given permission, and “The Search for the Missing Men” commenced.

After the war, she ran the Office of Missing Soldiers, at 437 ½ Seventh Street, Northwest, Washington, D.C., in the Gallery Place neighborhood. The office’s purpose was to find or identify soldiers killed or missing in action. Barton and her assistants wrote 41,855 replies to inquiries and helped locate more than 22,000 missing men. Barton spent the summer of 1865 helping find, identify, and properly bury 13,000 individuals who died in Andersonville prison camp, a Confederate prisoner-of-war camp in Georgia. She continued this task over the next four years, burying 20,000 more Union soldiers and marking their graves. Congress eventually appropriated $15,000 toward her project.

The American Red Cross

Clara Barton achieved widespread recognition by delivering lectures around the country about her war experiences from 1865 to 1868. During this time she met Susan B. Anthony and began an association with the woman’s suffrage movement. She also became acquainted with Frederick Douglass and became an activist for civil rights. After her countrywide tour she was both mentally and physically exhausted and under doctor’s orders to go somewhere that would take her far from her current work. She closed the Missing Soldiers Office in 1868 and travelled to Europe. In 1869, during her trip to Geneva, Switzerland, Barton was introduced to the Red Cross and Dr. Appia; he later would invite her to be the representative for the American branch of the Red Cross and help her find financial benefactors for the start of the American Red Cross. She was also introduced to Henry Dunant’s book A Memory of Solferino, which called for the formation of national societies to provide relief voluntarily on a neutral basis.

MARY ANN BICKERDYKE

Mary Ann Bickerdyke (July 19, 1817 – November 8, 1901), also known as Mother Bickerdyke, was a hospital administrator for Union soldiers during the American Civil War and a lifelong advocate for veterans. She was responsible for establishing 300 field hospitals during the war and served as a lawyer assisting veterans and their families with obtaining pensions after the war.

Early life

Mary Ann Ball was born on July 19, 1817, in Knox County, Ohio, to Hiram and Annie Rodgers Ball. She is cited as one of the first women who attended Oberlin College in Ohio, but official records show no proof of attendance. In 1847, she married Robert Bickerdyke, who died in 1859, two years before the Civil War. Together, the Bickerdykes had two sons.

She later moved to Galesburg, Illinois, where she worked as botanic physician and primarily worked with alternative medicines using herbs and plants. Bickerdyke began to attend the Congregational Church in Galesburg shortly after she became a widow.

Civil War service

in the Civil War from June 9, 1861, to March 20, 1865, working in a total of nineteen battles. Bickerdyke was described as a determined nurse who did not let anyone stand in the way of her duties. Her patients, the enlisted soldiers, referred to her as “Mother” Bickerdyke because of her caring nature. When a surgeon questioned her authority to take some action, she replied, “On the authority of Lord God Almighty, have you anything that outranks that?” In reality, her authority came from her reputation with the Sanitary Commission and her popularity with the enlisted men.

Dr. Woodward, a surgeon with the 22nd Illinois Infantry and a friend of Bickerdyke’s, wrote home about the filthy, chaotic military hospitals at Cairo, Illinois. The letter was read aloud in their church and Galesburg’s citizens collected $500 worth of supplies and selected Bickerdyke to deliver them (no one else would go). After meeting Mary Livermore, she was appointed a field agent for the Northwestern branch of the Sanitary Commission. Livermore also helped Bickerdyke find care for her two sons in Beloit, Wisconsin, while she was in the field with the army during the later part of the war. Her sons complained about living in Beloit.[5] She stayed in Cairo as a nurse, and while there, she organized the hospitals and gained Grant’s appreciation. Grant endorsed her efforts and detailed soldiers to her hospital train, and when his army moved down the Mississippi, Bickerdyke went, too, setting up hospitals where they were needed. Bickerdyke became a matron of the hospital in only five months.

She later joined a field hospital at Fort Donelson, working alongside Mary J. Safford. Bickerdyke cites Fort Donelson, specifically February 15 and 16, as the first battle she witnessed. At Fort Donelson, she realized that laundry services were lacking in the field hospitals. She packed up the soiled clothes and bedding that had been used by the men, added disinfectants, and sent it on a steamer bound for Pittsburg Landing to be cleaned by the Chicago Sanitary Commission. She also requested that her colleagues in Chicago send washing machines, portable kettles, and mangles. She then organized escaped and former slaves to provide laundry services for the hospitals she set up in the field.

After serving at Fort Donelson, she was appointed matron at Gayoso Block Hospital in Memphis. Gayoso had 900 patients, including 400 Native Americans. Like her other hospitals, “Mother” Bickerdyke employed escaped and former slaves at Gayoso. She had left Gayoso to run errands and returned to find the medical director had sent away the escaped and former slaves who helped her provide care for the hospital’s patients. She left for dinner but did not return right away. Rather, she visited General Hurlbut’s headquarters. She was given written authority to keep her employees until such time as Hurlbut himself revoked the order. She also set about acquiring cows and hens to provide dairy products for the hospital. General Hurlbut set aside President’s Island for their pasture and the escaped and former slaves cared for the animals.

Bickerdyke also worked closely with Eliza Emily Chappell Porter of Chicago’s Northwestern branch of the United States Sanitary Commission. She later worked on the first hospital boat. During the war, she became chief of nursing under the command of General Ulysses S. Grant, and served at the Battle of Vicksburg. As chief of nursing, Bickerdyke sometimes deliberately ignored military procedure, and when Grant’s staff complained about her behavior, Union Gen. William T. Sherman reportedly threw up his hands and exclaimed, “She outranks me. I can’t do a thing in the world.” Sherman acknowledged that she was “one of his best generals” and other officers referred to her as the “Brigadier Commanding Hospitals.” Sherman was especially fond of this volunteer nurse, who followed the western armies. Bickerdyke held the favor of both General Sherman and General Grant, who often provided her whatever she requested of them.

On October 27, 1863, Bickerdyke reported to Chattanooga and was witness to the battle of Lookout Mountain, nicknamed “the battle above the clouds.” “I watched the dreadful combat until the clouds hid all from view,” she wrote in a letter to Mary Holland, “In fancy I can hear General Hooker’s artillery now.” Bickerdyke set up the field hospital of the Fifteenth Army Corps for the Battle of Missionary Ridge, where she was the only female attendant for four weeks.] Part of her work during this campaign was to collect personal items of soldiers killed in battle and return them to the soldiers’ homes. On the march to capture Atlanta, Georgia, despite General Sherman’s orders to inflict “all the damage you can against [the enemy’s] war resource,” Bickerdyke worked to build hospitals for Confederate soldiers.

By the end of the war, with the help of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, Mother Bickerdyke had built 300 hospitals and aided the wounded on 19 battlefields including the Battle of Shiloh and Sherman’s March to the Sea. “Mother” Bickerdyke was so loved by the army that the soldiers would cheer her when she appeared. At Sherman’s request, she rode at the head of the XV Corps in the Grand Review of the Armies in Washington at the end of the war.

DORETHEA DIX

Dorothea Lynde Dix (April 4, 1802 – July 17, 1887) was an American advocate on behalf of the indigent mentally ill who, through a vigorous and sustained program of lobbying state legislatures and the United States Congress, created the first generation of American mental asylums. During the Civil War, she served as a Superintendent of Army Nurses.

Dix set guidelines for nurse candidates. Volunteers were to be aged 35 to 50 and plain-looking. They were required to wear unhooped black or brown dresses, with no jewelry or cosmetics.[30] Dix wanted to avoid sending vulnerable, attractive young women into the hospitals, where she feared they would be exploited by the men (doctors as well as patients). Dix often fired volunteer nurses she hadn’t personally trained or hired (earning the ire of supporting groups like the United States Sanitary Commission).

At odds with Army doctors, Dix feuded with them over control of medical facilities and the hiring and firing of nurses. Many doctors and surgeons did not want any female nurses in their hospitals. To solve the impasse, the War Department introduced Order No. 351 in October 1863.[32] It granted both the Surgeon General (Joseph K. Barnes) and the Superintendent of Army Nurses (Dix) the power to appoint female nurses. However, it gave doctors the power of assigning employees and volunteers to hospitals. This relieved Dix of direct operational responsibility. As superintendent, Dix implemented the Federal army nursing program, in which over 3,000 women would eventually serve. Meanwhile, her influence was being eclipsed by other prominent women such as Dr. Mary Edwards Walker and Clara Barton. She resigned in August 1865 and later considered this “episode” in her career a failure. Although hundreds of Catholic nuns successfully served as nurses, Dix distrusted them; her anti-Catholicism undermined her ability to work with Catholic nurses, lay or religious.

Her even-handed caring for Union and Confederate wounded alike assured her memory in the South. Her nurses provided what was often the only care available in the field to Confederate wounded. Georgeanna Woolsey, a Dix nurse, said, “The surgeon in charge of our camp … looked after all their wounds, which were often in a most shocking state, particularly among the rebels. Every evening and morning they were dressed.” Another Dix nurse, Julia Susan Wheelock, said, “Many of these were Rebels. I could not pass them by neglected. Though enemies, they were nevertheless helpless, suffering human beings.”

When Confederate forces retreated from Gettysburg, they left behind 5,000 wounded soldiers. These were treated by many of Dix’s nurses. Union nurse Cornelia Hancock wrote about the experience: “There are no words in the English language to express the suffering I witnessed today …”.

She was well respected for her work throughout the war because of her dedication. This stemmed from her putting aside her previous work to focus completely on the war at hand. With the conclusion of the war her service was recognized formally. She was awarded with two national flags, these flags being for “the Care, Succor, and Relief of the Sick and wounded Soldiers of the United States on the Battle-Field, in Camps and Hospitals during the recent war.”

MARY TODD LINCOLN

Mary Ann Todd Lincoln (December 13, 1818 – July 16, 1882)

served as the First Lady of the United States from 1861 until the assassination

of her husband, President Abraham Lincoln, in 1865.

Mary Todd was born into a large and wealthy, slave-owning

family in Kentucky, although Mary never owned slaves and, in her adulthood,

came to oppose slavery. Well educated, after finishing-school in her late

teens, she moved to Springfield, the capital of Illinois. She lived there with

her married sister Elizabeth Todd Edwards, the wife of an Illinois congressman.

Before she married Abraham Lincoln, Mary was courted by his long-time political

opponent Stephen A. Douglas.

Mary Lincoln staunchly supported her husband’s career and

political ambitions and throughout his presidency she was active in keeping

national morale high during the Civil War. She acted as the White House social

coordinator, throwing lavish balls and redecorating the White House at great

expense; her spending was the source of much consternation. She was seated next

to Abraham when he was assassinated in the President’s Box at Ford’s Theatre in

Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865.

During her White House years, she often visited hospitals

around Washington to give flowers and fruit to wounded soldiers. She took the

time to write letters for them to send to their loved ones. From time to time,

she accompanied Lincoln on military visits to the field. Responsible for

hosting many social functions, she has often been blamed by historians for

spending too much money on the White House.

Mary staunchly supported her husband in his quest to save

the Union and was strictly loyal to his policies. Considered a

“westerner” although she had grown up in the more refined Upper South

city of Lexington, Mary worked hard to serve as her husband’s First Lady in

Washington, D.C., a political centre dominated by eastern culture. Lincoln was

regarded as the first “western” president, and critics described

Mary’s manners as coarse and pretentious. She had difficulty negotiating White

House social responsibilities and rivalries, spoils-seeking solicitors, and

baiting newspapers in a climate of high national intrigue in Civil War

Washington. She refurbished the White House, which included extensive

redecorating of all the public and private rooms as well as the purchase of new

china, which led to extensive overspending. The president was very angry over

the cost, even though Congress eventually passed two additional appropriations

to cover these expenses. Mary also was a frequent purchaser of fine jewellery

and on many occasions bought jewellery on credit from the local Galt & Bro.

jewellers. Upon President Lincoln’s death, she had a large amount of debt with

the jeweller, which was subsequently waived and much of the jewellery was

returned.

The Lincolns had four sons of whom only the eldest, Robert,

survived both parents. The deaths of her husband and three of her sons weighed

heavily on her. Young Thomas (Tad) who died suddenly in 1871, had just spent

extended time traveling with her, after Robert married. Mary Lincoln suffered

with physical and mental health issues. She had frequent migraines, which were

exacerbated by a head injury in 1863. She likely suffered with depression or

possibly bipolar disorder. She was briefly institutionalized for psychiatric

illness in 1875, and then spent several years traveling in Europe. She later

retired to the home of her sister in Springfield, where she died in 1882 at age

63. She is buried with her husband and three younger sons in the Lincoln Tomb,

a National Historic Landmark.